Sunil Khilnani, Incarnations: India in 50 Lives. London: Allen Lane, Penguin Books, 2016. 636 pp. + xvii.

“India’s history”, Sunil Khilnani argues, “is a curiously unpeopled place. As usually told, it has dynasties, epochs, religions and castes—but not many individuals.” The colonial scholar-administrators who governed India through the first half of the 19th century, and their largely pedestrian successors, were firmly of the opinion that the individual as such did not exist in India. By the second half of the 19th century, colonial anthropology peopled India with “types”; in short time, India was then rendered a land of collectivities, where religion and then caste reigned supreme and the individual as an atom of being remained unknown. That, in good measure, would become the origin of ‘communalism’.

Statue of Aryabhata (c.476-550 CE), Indian astronmer, at the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Pune.

Mohandas Gandhi, one of fifty individuals who sits between the pages of Khilnani’s tome, was fully aware that in writing his autobiography, he was engaged in a task that was relatively novel to the Indian scene. He would, I suspect, have agreed that biography is another related genre at which Indians are spectacularly poor, though Khilnani seeks to rectify this shortcoming in this beautifully produced and elegantly written work which spans around 5000 years of history through fifty lives. There is no suggestion that other lives might not have been equally interesting, pointers to India’s complex and variegated history, and Khilnani advances a number of arguments to justify his choices. Many of India’s most compelling minds, he submits, have been compelled “to exist in splendid isolation”, and his endeavor is to put those lives into conversation with “other individuals and ideas across time and border”, though, as is often the case with Indian intellectuals, it is principally “the West” that he has in mind when he is thinking of cross-border exchanges and fertilizations.

There is also the more familiar argument that the omission of some well-known names allows Khilnani to rescue from obscurity some who scarcely deserved that fate. Thus, alongside the predictable pantheon of the greats—the Buddha, Mahavira, Akbar, Adi Shankara, Guru Nanak, Gandhi, Ambedkar, to name a few—we come across a slew of characters who are little remembered today. Among the more memorable of his cast are Chidambaram Pillai (1872-1936), a Tamilian lawyer whose Swadeshi Team Navigation Company created a sensation in nationalist circles before the British found a pretext for removing him from the political scene, and Nainsukh (1710-1784), a master of the Pahari school of miniature painting in whose work Khilnani finds ample evidence of humanity, warmth, individuality, and, most significantly, a modern sensibility.

A Share Certificate from the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company, Tuticorin, established by Chidambaram Pillai. [From the Hindu files.]

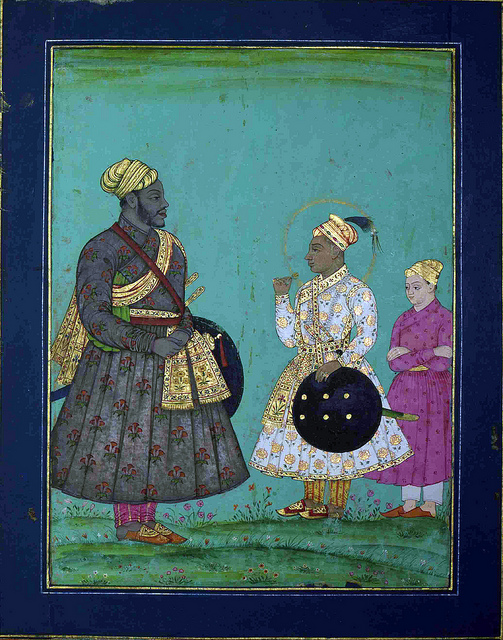

Murtaza Nizam Shah II, ruler of the Ahmadnagar Sultanate, and Malik Ambar.

Khilnani rather admirably is able to do justice to his subjects in comparatively short but crisp essays. On occasion, there are even startling insights or formulations. He writes of Jinnah with sympathy, but the critique in the concluding paragraph could not be more forceful: every dream of homogeneity is undercut by the fact that there is “some aspect of identity, some sect, some culture or language, that doesn’t fit”; in other words, “identity is prone to be secessionist.” The essay on Charan Singh, whose most thorough biographer is the American political scientist Paul Brass, is against the grain: he has been willfully forgotten, perhaps an index of the contempt in which recent governments have held the Indian peasant, but Khilnani is appreciative of his ability to command the voice of the peasants even if he is mindful of Charan Singh’s inability to speak for the landless farmer.

Everything in Khilnani’s charming book is reasonable—and that, perhaps, defines the limits of his imagination. About everyone gets the same number of pages, and one could say that the king (Ashoka, to name one) and the pauper (Kabir) are treated with radical equality. No man (or woman, though there are few and far between) is treated with reverence as such. Criticisms of Gandhi are these days dime a dozen, but even the Buddha is reprimanded for exhibiting patriarchal values. The principle of selection is anodyne at worst and liberal at best. It is, after all, a mark of the liberal sensibility that one should be able to view one’s subject with warts and all, and Khilnani is scrupulous in the observance of this principle. The accent is unquestionably on the modern: nearly thirty of his fifty individuals, commencing with Rammohun Roy, lived in the 19th and 20th centuries. Doubtless, modern lives are better documented, but perhaps Khilnani reveals something of his sensibility in his predilection towards the modern. He bemoans the fact that Indian women’s lives are not well documented, but one might counter by asking why Razia Sultan, Sarojini Naidu, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, and Lata Mangeshkar are omitted from his narrative. There is, however, a greater problem: if Khilnani is constrained by his sources from speaking about women, he is surely not precluded from venturing into the politics of gender, femininity, and masculinity. There is precious little of that in Incarnations, since he lets a rather elementary even procrustean conception of women’s lives guide his treatment of gender.

As with an anthologist, one should perhaps not begrudge Khilnani his choices. There is a perfectly good reason why each of those fifty Indians becomes one of Khilnani’s “Lives”, though one should not imagine that they are necessarily, in Emerson’s phrase, “representative men”. It is not as if Kabir is representative of the nirguna bhakta while Mirabai is the preeminent voice of saguna bhakti, assuming that the vast swathe of what is called the “bhakti movement’ may be divided into these two camps. Nevertheless, as Khilnani himself would recognize, one can be certain that much of the animated discussion of his book will revolve around his choices, and some will deplore the absence of their heroes while others will wonder why a Sheikh Abdullah is being placed in the lofty company of Gandhi or Ambedkar.

Rammohun, Vivekananda, Tagore, Satyajit Ray: one can have only so much of (as someone once quipped) the still-continuing Bengal Renaissance. If one were attempting, say, 50 American Lives, I think it quite likely that Muhammad Ali and Babe Ruth would certainly have made the cut if not Michael Jordan and Jackie Robinson. Yet, not a single sportsperson is represented in Khilnani’s Incarnations, though for two decades the hockey wizard, Dhyan Chand, made millions of Indian hearts flutter.

Dhyan Chand, India’s “Hockey Wizard”.

P. T. Usha never won India a single Olympics medal, not even a measly bronze, yet for a decade the hopes of an entire country were invested in her. The chest-beating that takes place in Indian middle-class homes every four years, when a country of much more than one billion finds itself possessed of a medal or two, outclassed by countries such as Belarus, Georgia, and Jamaica, points to the deep anxieties that afflict the Indian middle class. Had Khilnani been attentive to the politics of recognition, it is quite likely that he would have come up with quite a different set of Indian lives.

[A slightly different version of this review has been published in The Indian Express, 2 April 2016, as “From Aryabhata to Vivekananda”.]

Dhyan Chand might indeed be a deplorable omission, but Milkha Singh arguably even more so, given that the “Flying Sikh” was the “only Indian male athlete to win an individual athletics gold medal at a Commonwealth Games” until as late as 2014 Games, according to Wikipedia.

And as for the women left out of Khilnani’s book, ostensibly because of the lack of biographical material about them, surely there’s enough factual information on Jhansi ki Rani Lakshmi Bai.

LikeLike

Hi Ajay,

I did not say in the review that there are no women represented in the book; I said that they are “few and far between”. I do not, of course, mention all the 50 Lives, something you would find enumerated in the book’s table of contents. The Rani of Jhansi is, in fact, included in “Incarnations”. My point about Dhyan Chand and P T Usha is somewhat different than what you infer, and does not have much to do with whether a person earned a medal or not. (If it were a question of medals, Milkha is not a patch on Dhyan Chand; India won the hockey gold in every Olympics where he played.) Dhyan Chand captured the imagination of a country like no other sporting figure for more than a decade, and this before cricket became ascendant. Milkha Singh was certainly in the news, too, but it would be interesting to ask whether he ever was, so to speak, the heart-throb of the nation in the way in which P T Usha was, for instance. The relatively recent biopic on Milkha has made him familiar to Indian audiences once again, but I think Dhyan Chand occupied a very different place in the nation’s imagination, and that at a time when India was still under colonial rule.

Moreover, I’m not suggesting that his omission from Khilnani’s book is “deplorable”; rather, I’m questioning what it is that gives a person “recognition” and what is the politics of such recognition. Cheers, Vinay

LikeLike