(First in a series of articles on the implications of the coronavirus for our times, for human history, and for the fate of the earth.)

Wuhan on 3 February 2020. Getty Images; source: https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-wuhan-relaxes-quarantine-immediately-reverse-2020-2

The social, economic, and political turmoil around the COVID-19 or coronavirus pandemic presently sweeping the world is unprecedented in modern history or, more precisely, in the last one hundred years. Before we can even begin to understand its manifold and still unraveling ramifications, many of which are bound to leave their imprint for the foreseeable future, it is necessary to grasp the fact that there is nothing quite akin to it in the experience of any living person. Fewer than 5500 people have died so far, and of these just under 3100 in the Hubei province of China. There have been hundreds, perhaps a few thousand, wars, genocides, civil conflicts, insurrections, epidemics, droughts, earthquakes, and other ‘natural disasters’ that have produced far higher mortality figures. About 40 million people are estimated to have died in World War I; in the Second World War, something like 100 million people may have been killed, including military personnel, civilians, as well as those civilians who perished from war-induced hunger, famine, and starvation. Weighed in the larger scheme of things, the present mortality figures from COVID-19 barely deserve mention. And, yet, it is possible to argue that what is presently being witnessed as the world responds to the COVID-19 is singular, distinct, and altogether novel in our experience of the last one hundred years.

Why should that be the case? It would be a truism to say that no one ever quite expected something like the coronavirus to spring upon us and, virtually overnight in some places, alter the entire fabric of social existence. In 1994, an intrepid journalist and researcher, Laurie Garrett, published a voluminous book, The Coming Plague, subtitled “Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance.” Written a few years after AIDS rudely awakened the world to the fact that our war with microbes is relentless, and that modern science’s supposed conquest of infectious diseases is a fantasy, Garrett argued that there was every likelihood that new and more lethal diseases would emerge, unless human beings adopted a perspective that would be more mindful of a “dynamic, nonlinear state of affairs between Homo sapiens and the microbial world, both inside and outside their bodies.” In his introduction to the volume, Jonathan M. Mann, Professor of Epidemiology and International Health at Harvard, and Director of the Harvard AIDS Institute, suggested that AIDS “may well be just the first of the modern, large-scale epidemics of infectious diseases.” If air travel has become possible for over a billion people, infectious agents can also be introduced into “new ecologic settings” far more easily. If AIDS has a lesson to teach us, Mann warned twenty-five years ago, it is that “a health problem in any part of the world can rapidly become a health threat to many or all.”

If Garrett and Mann, and perhaps a handful of other people here and there, may have been prescient, still the scope of the worldwide panic and emergency in which we are all trapped is outside the realm of contemporary human experience. The first death from the coronavirus was reported in Hubei province, which has a population just short of 60 million, on 10 January 2020. The notice announcing the closure of all transportation services in Wuhan, the largest city of the province with 11 million people, was issued early on January 23 and had been virtually put into effect later in the day; and by the end of the following day, nearly the entire province had been sealed off. Further orders on February 13 and 20 shut down all non-essential services, including schools, and a complete cordon sanitaire had been placed around a province with as many people as Italy, which has now become the site of the next largest outbreak.

What has transpired in Italy has been not any less dramatic. At the end of January, only three cases had been detected in Italy, and two of these were Chinese tourists. The patients were isolated and Italy moved to halt flights from China: as the Italian Prime Minister declared to the world on January 31, exuding supreme confidence, “The system of prevention put into place by Italy is the most rigorous in Europe.” A more ill-timed comment can scarcely be conceived; the disease was slowly working its way through the population—undetected , unheralded, unheeded. Until nearly the end of the third week of February there appeared to be only a handful of cases; then, within days, the numbers of those infected skyrocketed. Italy, many are likely to forget, is a country of old people; it has a negative fertility rate and a declining population. Those most susceptible to the coronavirus are the elderly, and those whose lives have been claimed are overwhelmingly among the elderly. Italy has now over 17,000 confirmed cases and over 1200 deaths. First the northern region of Lombardy was put under severe restrictions; on March 9, the entire country was placed under lockdown, shutting down everything except some essential services, pharmacies, and selected supermarkets.

Piazza Navona, central Rome, 12 March 2020, after the enforcement of the lockdown over all of Italy. Image copyright: VINCENZO PINTO/AFP via Getty Images

Italy’s streets and famous piazzas are now deserted, but the world’s most popular tourist destination seems to have set the cue for the rest of the world. Over thirty countries, in recent days, have shut down universities, schools, amusement parks, and museums, and forbidden public gatherings—in many cases, for a month or longer. There is every possibility that, in the days ahead, major cities, in the US, Europe, India, the Middle East, and elsewhere will come under lockdown, just as schools, universities, and public and private institutions of every imaginable stripe—corporations, art galleries, government offices—in other countries follow suit. And therein lies the singularity of the social response to COVID-19: at the height of wars, disasters, and national emergencies, schools and universities have rarely shut down for such extended periods of time. Our instinct, in the face of emergencies, is to band together, to seeks communities of cohesion: but the present virus demands extreme social isolation.

If I have described the social response to COVID-19 as unfathomable in the experience of any human being who is alive, it is because for a precedence we would have to turn to the influenza epidemic of 1918-19, altogether misleadingly nicknamed the “Spanish Influenza” for no other reason than the fact that the most reliable news about this pandemic, which waxed and waned for over one year, came out of Spain which remained neutral during the war. It was then believed to have taken 20 million lives; but researchers over the last two decades have suggested that the death toll from it was between 50-100 million. Strangely, though this influenza pandemic killed more people worldwide than did World War I, it quickly became “the forgotten pandemic”—and remains so. Nowhere did it strike as hard as in India, where poverty, disease, poor nutrition, and the lack of preventive medical care rendered many—who can be differentiated along caste, class, and gender lines—extremely vulnerable. Some 18 million Indians, or 7 percent of the population of undivided India, are estimated are estimated to have died from this flu.

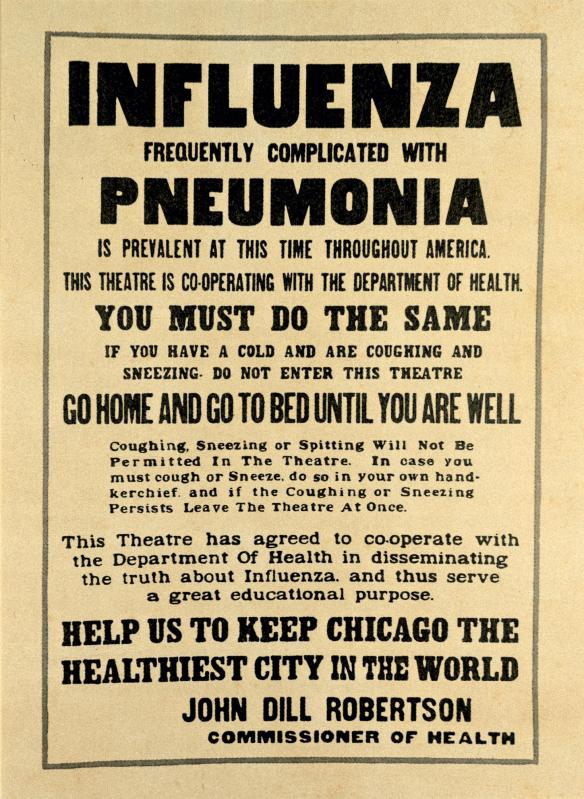

Coughing, Sneezing, Spitting: No Laughing Matter: Wash Your Hands, Stay at Home — A Poster issued by the Chicago Commissioner of Health during the Influenza of 1918-19.

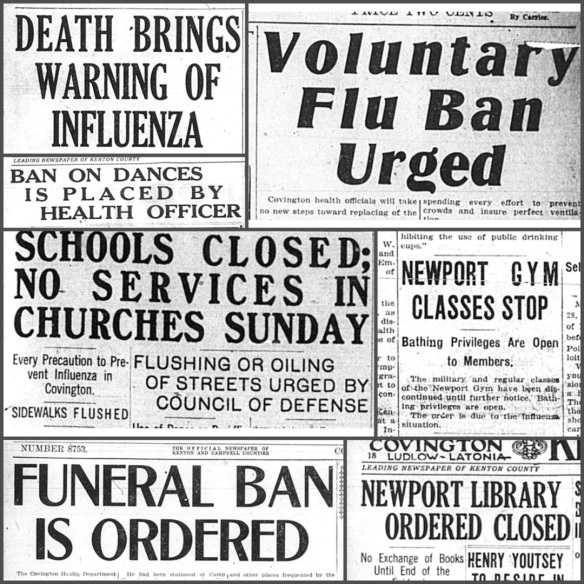

It is, thus far, not the mortality rate which makes the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 the true predecessor of COVID-19. Modern medicine has doubtless progressed very far in the intervening century, but even then it was understood that the creeping invasion of the virus could only be halted by enforcing quarantine and social isolation. Holcombe Ingelby, Member of Parliament from Norfolk, wrote to his son on 26 October 1918: “If any of your household get the ‘flue’, isolate the culprit & pass the food through the door! It is rather too deadly an edition of the scourge to treat it anything but seriously.” Around 200,000 people died in Britain; in the US, where the death toll was at least three times higher, Surgeon-General Rupert Blue strongly advised local authorities to “close all public gathering places if their community is threatened with the epidemic.” The mayor of Philadelphia, then the third largest city in the US, ignored the advice; the mayor of St. Louis, then the fourth largest American city, shut down “theaters, moving picture shows, schools, pool and billiard halls, Sunday schools, cabarets, lodges, societies, public funerals, open air meetings, dance halls and conventions until further notice.” The list of venues and institutions tells another tale; what is more germane is that, at its peak, the fatality rate in Philadelphia was five times higher than in St. Louis.

Some headlines from the Kentucky Star and Kentucky Times-Star, 1918-19, about the “Spanish Flu”. Source: https://www.nkytribune.com/2016/09/our-rich-history-spanish-flu-pandemic-of-1918-19-the-granddaddy-of-all-flu-outbreaks-in-nky/

The epidemiology of the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 still remains something of a mystery. We likewise know comparatively little about COVID-19, though Chinese scientists had by mid-January shared its genome sequence with the world. But it appears that enough is known to establish that the protocols of self-isolation, quarantine, and social isolation will be crucial to stem its spread and eventually bring it under control. It is easy to underestimate the coronavirus, as Donald Trump has done by dismissing it as something that will disappear miraculously; but it may also be that pronouncements about the tens of millions who may be infected and may die augur a morbid outlook that, even as we are with due reason inclined to reject, points to the likelihood that the coronavirus brings to the fore critical questions which have been lingering around and will have to be addressed more openly. These questions—the implications of “social isolation”, the impact of the virus on the poor and low-wage workers, the question of “porous” and “closed” borders, the deployment of authoritarian models of social control, the future of globalization, and myriad others—will now confront us with renewed urgency.

First published under the same title at abpliv.in, here.

Also published in Hindi here as कोरोना वायरस की विलक्षणता और असाधारणता जिसने दुनिया को झकझोर दिया

Hope you and your family are managing well w/Coronavirus. On a side note – have you written about the collapse of the Left in India (CPI-M and others) and how was a harbinger of the rise of the BJP?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Fragments of History.

LikeLike

I appreciate you doing this series. I was just talking to someone about the all the cultural output that will come from this astonishing moment in time. This is one example of that.

LikeLike

Very good information.

For Latest Telugu News on Corona, please visit

https://www.hmtvlive.com/telangana/coronavirus-test-center-has-started-in-kakatiya-university-telangana-41389

LikeLike

It is crazy to see what the numbers were for deaths caused by COVID-19 when this blog was written compared to now. According to the blog, “fewer than 5500 people” had died when this was written. Currently, about 3.5 million people have died due to the coronavirus. I do not think any of us could have predicted how drastically this virus would affect people in every corner of the world. It is definitely true, as stated here, that no one expected something like COVID-19 to spring upon us so suddenly. I remember first hearing about it while I was in one of my high school classrooms when it hit Italy and everyone, myself included, totally ignored the severity of it and brushed it off as another “flu”. Yet today, people continue to work from home, learn through Zoom, and wear masks routinely. It is so strange to think back to a time, even when COVID-19 had hit certain places such as China and Italy, where we were going about our daily lives, no masks and unexpecting of what was to come. It truly has changed everyone and will go down in history as a time of uncertainty and disarray. “Our instinct, in the face of emergencies is to band together, to seek communities of cohesion: but the present virus demands extreme social isolation.” I thought this quote basically summed up what the coronavirus experience has been like for many people: a time where we are removed from the world around us and are forced to shape our lives around an invisible, yet powerful influence.

LikeLike

Hello Professor Lal!

Looking back at the rise of COVID-19 is so surreal for me. When the disease first spread in China, I was just starting the second semester of my senior year, looking forward to that covenanted prom and graduation. Instead, I recall, things slowly started closing: my swimming team practices were canceled, emails sent out regarding increased sanitations, and then days were taken off. But these days turned into weeks, weeks into months, and before I knew it, my high school announced the rest of the semester would be online.

We never had a graduation, nevermind a prom.

As the summer rolled around, I was furloughed from my work as a lifeguard and I spent the better part of my days at home, sitting in front of a computer screen. College changed very little, and my entire freshmen year has been taken online. And to be honest, it feels like I’m still in high school.

Indeed, my refection is made worse when I considered the obstacles we encountered as a nation in anti-vaxxers and other deniers. As I head into the second year of college for me, I hope that I finally get to see my campus and actually experience college to its fullest. However, COVID-19 will forever remain in my memories, and a story I’m sure to tell my children in the times to come.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this essay quite a lot! I must admit that it was quite strange reading this essay now, especially considering the world is slowly opening up again. The images of headlines and posters during the Spanish Influenza pandemic that are woven in throughout this writing are eerily similar to the messages that were spread throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early months of 2020, a relatively small amount of people expected the pandemic to last well over a year. It appears to me now that this may have been a result of leaders downplaying the dangerous nature of the coronavirus. The series of questions presented at the end of the essay are perfect examples of the issues that people faced during the pandemic. Unfortunately, the pandemic was dealt with quite poorly by the United States. The poor continued to get even poorer, citizens were socially isolated for well over a year, and a disturbing number of people passed away due to complications from the virus. It is interesting to think about what the world would look like if we took the virus seriously and the pandemic actually ended in a month or so. The pandemic certainly left a terrible impact on the world that will be remembered for generations to come.

LikeLike

The novelty of our relationship with the Coronavirus was certain to cause issues in our lives as social animals, yet the variety of was in which it sparked controversy were unexpected to say the least. Perhaps it only appears this way to me as I am an American residing here and consuming American media, but it seems to me that the U.S. public had much more brash responses than most other countries despite not breaking the top 10 confirmed cases-per-million around the world. The shockingly widespread anti-mask sentiment here in the U.S. seems to be a fairly unique situation among the world’s nations. It is a fascinating social phenomenon and one that certainly warrants study. I wonder how the politics of small government have become so deeply ingrained in some people’s brains that they would put themselves and others at risk of death so as to not become some undefined “pawn of the government”.

LikeLike

It’s really interesting to read this article which was written in the very early days of the pandemic and see its predictive powers now that the pandemic has lasted for over a year and a half. I think what was particularly interesting is your main point in the paper asserting that the covid pandemic stands out as an exceptionally significant and unprecedented event in history because of the complete economic shutdown of the entire world economy during the start of the pandemic and the complete social isolations in many countries throughout the pandemic. In this respect, it’s definitely true that the pandemic’s impact on civilian life has gone beyond war times in terms of closure of public facilities. However, the pandemic also is unique in the sense that all political powers in the world are largely united and cooperative in fighting the external virus minus the exceptions of capitalist greed and vaccine politics, whereas in many major wars, not only are the casualties much higher, the political and economic tensions between foreign nations are also incomparable to the current covid pandemic.

Another interesting impact of lockdown and the ongoing pandemic is the modifications of social interactions, creating almost a cultural shift in the way we greet and interact with each other. It remains to be seen whether after widespread vaccinations whether we will return to normal or forever be changed in the ways we socially interact with one another.

LikeLike

You are right that in consequence of the pandemic the norms of social behavior might change though it is too early to say that and I suspect that we will revert to how things were before the pandemic. We also don’t know enough about how norms of conduct changed after, for instance, the Black Death, to say whether the present pandemic is very different, though in my book “The Fury of Covid-19” (2020) I suggest that this cannot be the grounds on which we view the present pandemic as unique. You are similarly right that there has been international cooperation at a very great level but here again the worldwide efforts to eradicate smallpox and polio set the template. For a more exhaustive view of these matters, I refer you and other readers to my aforementioned book.

LikeLike

Wow. The impact of COVID now versus the first warnings signs talked about in this article is astonishing. Little over a year ago, the death toll was in the thousands compared to 3.8 million now (and over 176 million cases total). Interestingly enough, I have a unique fascination with viruses; in high school I ended up reading The Hot Zone by Richard Preston on a whim and ever since I’ve been enthralled by the concept of viruses. A book about the emergence of AIDS, Ebola and other viruses, the author argued that many of the known rain-forest viral infections were Earth’s response to humanity’s constantly escalating ecological destruction. More importantly and to the point, he warned that epidemics and outbreaks are far too often overlooked and quickly forgotten, a fact that even I (an individual who had once been fascinated with the subject) had already discarded from my memory. The fact that you echo this sentiment here is worrisome in that I wonder how long it will take before the impact of COVID is overlooked and relegated to the same worry we extend to say AIDS (a virus that has been put on the relative back-burner in terms of attention and importance, despite there being 690,000 deaths associated with it in 2020 alone).

LikeLike

Hi Professor Lal,

Pandemic could never be discussed enough, as it tells a lot about the strength and weakness of our humanity. The most interesting part that stood out to me was when you illustrated an example about Spanish Influenza. There I see a lot of similarities. I think any kinds of plague show the pre-existing inequality, and it was very interesting to see how a case in 20th centry was not an exception. The socially disadvantaged composed the largest portions of the infected people, which astonishingly resembles what we experienced during the most recent pandemic.

Your blog, overall, teaches me the impact of pandemic is more about the societal function than medicine. In a situation where an unknown virus emerges, it’s rather the societal measure that determines the consequences, as the medical measures come relatively later.

LikeLike

Hi Professor. Reading your article brought back a lot of memories during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though it was so long ago, at the same time it feels like it could have been yesterday. I remember sitting in class and being told that the school would shut down for 2 weeks which turned into a year and a half. Additionally, I really like how you used the flu to relate to the events occurring with COVID-19. I find it quite fascinating the signs and posters they were using back then to warn people about the flu. I’m sure it would be interesting to investigate the way in which information was distributed back then versus today with social media and other news outlets. It would also be cool to delve deeper into the methods used to prevent the spread of the flu back then versus the methods being used today to counteract COVID-19. It’s also worth mentioning how this paper was written early on in the pandemic and how much greater the response to the virus became just days and weeks later. The death tolls now are some much greater and I’m sure that they are still rising.

LikeLike

It is incredible how this paper was written at the very start of the pandemic and now I am reading this a little over 3 years later. No one in the world knew when this epidemic was going to and and how many of us were going to come out alive. It is impossible to predict that as of May 11, 2023 would mark the “end of the pandemic”. Although, Covid-19 is still a very serious matter, it is no longer considered an emergency. The uneasiness of the pandemic ignited fear all over the world. It is remarkable how some of the posters that were seen during the Spanish Influenza is, or rather, was seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. Every store you went into, every post on social media, and every news channel was plastered with the same messages encouraging people to stay home and to use a face mask. Every news channel has a live count of those affected and those who unfortunately lost their battle to the virus.

As Professor Lal stated, “It is easy to underestimate the coronavirus,” he was not wrong, but as a society, I deeply regret that we did not do enough or people did not take it seriously enough. The Covid-19 virus was deadly and took countless lives, some very close to me.

LikeLike