(in multiple parts)

Part I of A Global Plague, Political Epidemiology, and National Histories

(Sixth in a series of articles on the implications of the coronavirus for our times, for human history, and for the fate of the earth.)

COVID-19 has made diarists of many of us, but the Englishman Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was, to use a contemporary expression, far ahead of the curve. Pepys, who lived through the Great Plague that struck London in 1665-66, as well as the Great Fire of London that over the course of five days in September 1666 gutted the old City of London, was a prodigious keeper of a diary that remains unrivalled in its depiction of the daily life of a well-heeled and influential man living in times of turmoil and pestilence. Pepys might well have been writing about the pandemic that has crept upon us: there is an uncanny resemblance to our times in his observations of how an epidemic insinuates itself among a people, the measures that were undertaken to effect its containment and mitigation, the pallor of death that hangs over an entire society when plague strikes, and what a plague brings out in a people and a nation.

Portrait of Samuel Pepys in 1666 by John Hayls

Pepys commenced his diary on January 1, 1660, and on 19 October 1663 first mentions the plague as having reached Amsterdam. The following year, on June 22, Pepys recorded that there was “great talk” at the coffee-house which he was fond of frequenting of “the plague [which] grows mightily among them [the Dutch], both at sea and land.” On July 25th, his visit to the coffee-house yielded “no news, only the plague is very hot still, and increases among the Dutch.” What impresses most thus far is that there is no intimation of the plague coming to the shores of England: perhaps the island was shielded, after all, from every pestilence coming from the continent. The Dutch and the English had been at war in 1652-54, and another conflict was looming on the horizon between the two naval powers competing for trade, overseas colonies, and supremacy on the seas. There is thus something of a suggestion of the Dutch being the source of many of England’s troubles: if they had already brought the plague of war, another form of pestilence seemed to be at hand. Pepys, a Member of Parliament and Chief Secretary to the Admiralty whose reforms would play a significant role in transforming the English navy, to the extent that the Royal Museums Greenwich website states that he is “often described as ‘the father of the modern Royal Navy’”, would also have known that the plague sails with ships—and that England was not likely to be spared.

Another year, and the rats had made their way to the city as his entry for April 30th 1665 shows: “Great fears of the Sicknesses here in the City, it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all.” June 7th was “the hottest day”, Pepys wrote, that he had ever felt in his life but the afternoon brew he had at the “New Exchange” did little to cheer him up: he did in Drury Lane “see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ writ there—which was a sad sight to me, being the first of that kind that to my remembrance I ever saw.” Henceforth, the plague would very much be on Pepys’ mind: three days later he describes himself “being troubled at the sickness”, and thinking that he should put his papers in order “in case it should please God to call me away.” Those households where the plague had claimed a victim were evidently marked, so that others might keep their distance from them: it was, as an aside, this very idea of the untouchability of those homes that the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant invoked to mark the inviolable sanctity of those carrying out relief work when he founded the Red Cross. But with every entry Pepys adds something new to our understanding. That the plague had made its way into the city, and into his own life, is brought home to Pepys when, on June 10th, he is troubled “mightily” to discover that it should have begun at the home of his “good friend and neighbour’s, Dr. Burnett in Fanchurch Street”—and that five days later the number of dead should have risen to “112, from 43 the week before.”

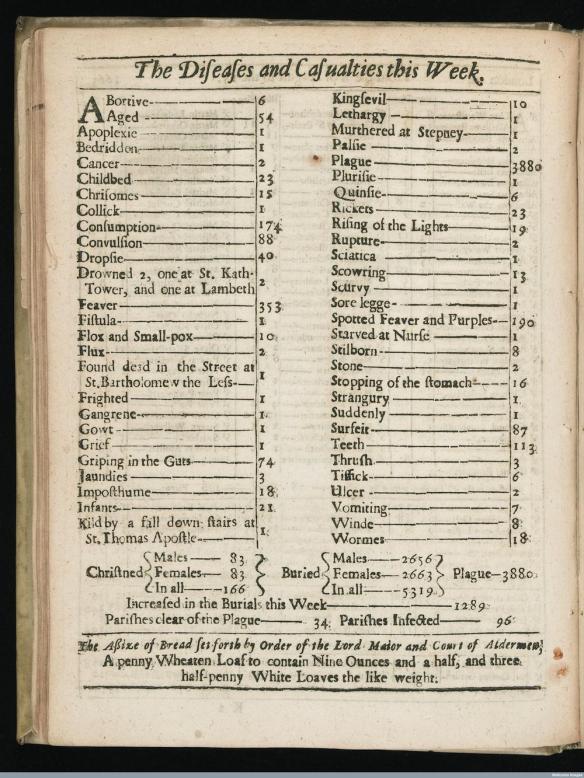

The Bill of Mortality for the week of August 15-22, 1665, with 96 of 130 parishes reporting being affected by the plague. The mortality figures from the plague (3880) are found in the bottom right.

There, in Pepys’ account of the creeping sometimes sinuous rise of the plague, which before it petered out in late 1666 had claimed perhaps as many as 100,000 Londoners, wiping out a fourth of the city’s population, we begin to see the contours of so much of the present writing on the coronavirus pandemic. His invocation of its simultaneous proximity and distance is striking: “but where should it begin” but at the home of a friend, Pepys writes, and on June 17th its uncomfortable proximity to his own life is brought home to him when he takes a ride home in the afternoon: “It struck me very deep this afternoon going with a hackney coach from my Lord Treasurer’s down Holborne, the coachman I found to drive easily and easily, at last stood still, and come down hardly able to stand, and told me that he was suddenly struck very sick, and almost blind, he could not see”. But for all his empathy for the coachman, Pepys was not about to minister to the sick man: “so I ‘light [alighted] and went into another coach, with a sad heart for the poor man and trouble for myself, lest he should have been struck with the plague . . . but God have mercy upon us all!”

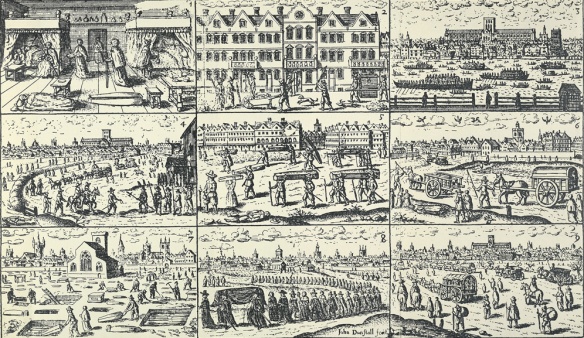

Scenes from life in London during the Great Plague, 1665-66, from the collection of the Museum of London.

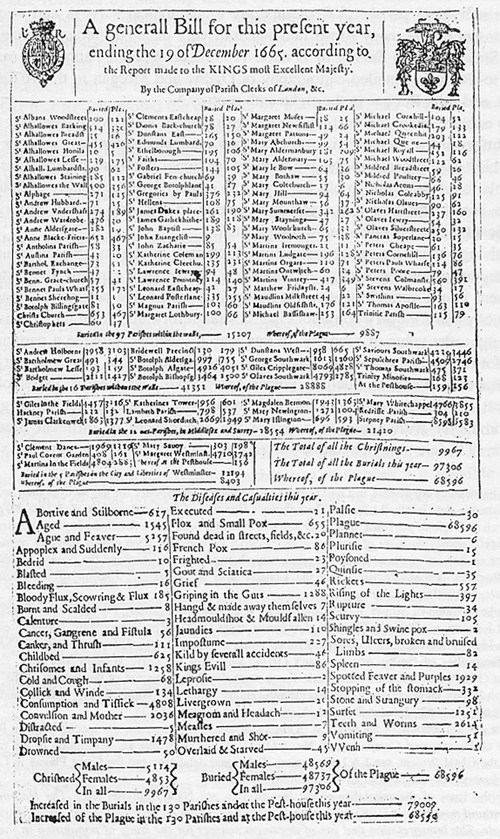

Pepys not only removed himself from a situation where his own health might have been compromised with alacrity, but he had already moved into the enumerative mode, counting the number of the dead; indeed, as days yield to weeks and then to months, he displays an obsessiveness with recording the weekly toll of dead displayed on the “Bills of Mortality” plastered on city walls. These Bills of Mortality, another contemporary wrote, furnished a picture to their readers “in the Plague time how the sickness increased or decreased, so that the rich might judge of the necessity of their removal, and Tradesmen might conjecture what doings they were likely to have” (John Graunt, Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality, London, 1662). The plague grew (in Pepys’ favorite word) “mightily”: the number of dead in one week, the entry for July 31 states, had gone up to “1700 or 1800 of the plague”, and by the week that brought August to an end, “7496” had died in the city, “6102” of the plague: but it is feared, Pepys would state, as if in anticipation of the uncertainty with which the mortality count from the coronavirus is being placed before us, “that the true number of the dead this week is near 10000 – partly from the poor that cannot be taken notice of through the greatness of the number, and partly from the Quakers and others that will not have any bell ring for them.” We want to know, always, the “true number”: is it out of a fidelity to the truth, a trust in numbers, the fear of the waves crashing upon us, as a social fact to be used to some end, or in the scarcely acknowledged morbid fascination we experience in seeing the numbers shoot up and thus reminding us that we are living in the midst of a momentous event that is truly one for the history books? Should we be surprised that, in Wuhan and New York city alike, the number of those dead from the virus has been revised upwards, and that the bell will not toll for the poor when they drop off like fleas?

The bill of morality for the year ending 31 December 1665. The horrendous loss from the plague is reported on the bottom right.

“A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths are a statistic”: so Stalin is alleged to have said, and it matters not a jot if the apothegm is apocryphal. Statistics produce one kind of distancing, but the entry for September 14th in Pepys’ diary points to the other registers of moral distancing. The dead were being carried past Pepys as he took to the streets for his walk; the alehouse that was his other abode was shut up; and then perforce he had to “hear that poor Payne my waterman [river worker] hath buried a child and is dying himself – to hear that a labourer I sent but the other day to [the London borough] Dagenhams . . . is dead of the plague and that one of my own watermen, that carried me daily, fell sick as soon as he had landed me on Friday morning . . . is now dead of the plague – to hear . . . that both my servants, W Hewers and Tom Edwards, have lost their fathers . . . of the plague this week”: all this put Pepys “into great apprehensions of melancholy, and with good reason.” The dead are pitiable; it is also their closeness to him that makes Pepys feel apprehensive, and for a moment even contemplate the loss as his own; and yet he must distance himself from them lest they should contaminate him. As a man of considerable means, much like the super wealthy in California and Manhattan’s Upper East Side who have fled for their country homes or private yachts in the wake of COVID-19’s onward march, Pepys could settle his wife in a country home and himself retreat to the countryside when the occasion demanded—though not without some sleight of hand. Word of the plague had spread and people were “afraid of London, being doubtful of anything that comes from thence or that hath lately been there,” and Pepys found that he had no expedient but to say that he “lived wholly at Woolich.”

What is most remarkable, however, in Pepys’ recounting of the Great Plague is that even as the disease continued to decimate the city, he carried on with life as usual. He was up and about town, stopping by the stationers, settling accounts with merchants, stocking his cellar, exchanging political gossip, and dining with friends. On September 9th, just days before his lamentation about the deaths of those known to him which put him in a mood of great apprehension, he was off to lunch at Lord Brouncker’s where the party feasted on “venison pasty” and everyone was “mighty merry.” Less than two weeks later, on September 20th, he was again at Brouncker’s home, where the diners included a certain Lady Batten—who, says Pepys with evident titillation, was on good terms with a certain Mrs. Williams, “my Lord Brouncker’s whore”—and all “were mighty merry.” Pepys was quite the philanderer, eyeing one of the King’s own mistresses and even carrying on with the house maids under his wife’s nose: the stench of the dead from the plague did nothing to diminish his appetite even for the common wench.

Under order of Charles II, no stranger was to be permitted in London without a certificate of health, public funerals were outlawed, “unwholesome Meats, stinking Fish, Flesh, musty Corn” were forbidden from the marketplace, infected homes were to be “shut up for forty days”, and warders were to be appointed to prevent the unhealthy “from conversing with the sound.” Nevertheless, as is amply demonstrated by the 1666 “Rules and Orders to be observed by all Justices of Peace, Mayors, Bailiffs, and other Officers, for prevention of the spread of the infection of the PLAGUE”, as much as by Pepys’ diary, Charles II did not envision the shuttering of England’s economy and social life. Quite pointedly, the Orders, to take one illustration, allowed for the explicit provisioning of alcohol, stating only “that no more Alehouses be Licensed then are absolutely necessary in each City or place, especially during the continuance of this present Contagion.” Pepys moved around town as someone who prized his liberty and, while mindful of the restrictions placed by the state, did not wish to be unduly hampered in his movements. Moreover, with the diary as his testament, it is clearly the case that many business establishments remained open. One might say that, in his time, much less was known than at present about how disease is spread, and bubonic plague is more likely to take as its victims those who live in rat-infested dwellings and unhygienic conditions. Pepys may have seen little reason to fear for his life, and the generic homilies—“God save us all”, or “The Lord knows what will become of us”—with which he peppers the plague entries in his diary might rightfully be seen for the predictable expressions of piousness that they are.

Note: Spellings from Pepys’ diary have been modernized; and Bruncker is written as Brouncker.

(to be continued)

Lots of data and details. Interesting read, thanks.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Pub Crawl and the Sprint of the Virus: Britain, COVID-19, and Englishness | Lal Salaam: A Blog by Vinay Lal