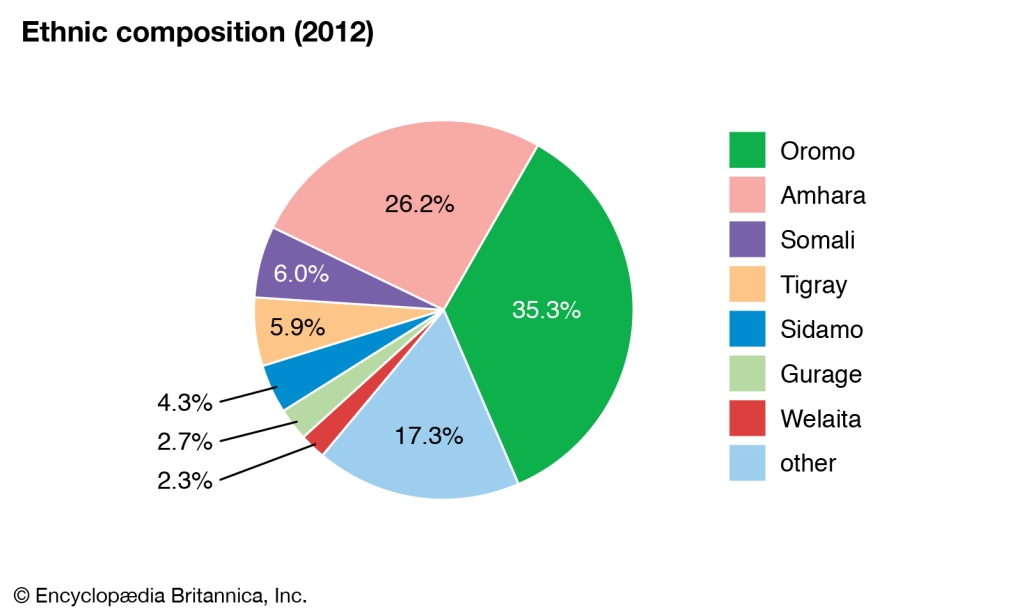

Ethiopia, a country of around 115 million people, has been over the last few weeks in the thick of a civil war that, the Ethiopian government submits, is now drawing to a close. The attempted secession of the Tigray region has apparently been thwarted by decisive military action. It remains to be seen whether the proclamation of victory is justified or premature, but what has been unfolding there should be of special interest to multiethnic states and particularly democracies which are struggling to contain the rising tide of ethnic particularism and xenophobia which is sweeping the world. For most of the 20th century, the Amhara, with 27 percent of the population, held sway over a country with seventy ethnic groups, among them the Oromo (34%), the Tigray (6%), and Somalis (6%). The more than four decades long rule of Haile Selassie was brought to an end in September 1974 when the 82-year old Emperor was deposed and a military junta known as the Derg assumed power. Ethiopia was transformed into a single party Marxist-Leninist state. For much of that period, the country became indelibly linked, in the worldview of the outsider, with the image of famine; internally, the “Red Terror”, the campaign of repression unleashed by Mengistu Haile Mariam, the Derg’s point man, made short work of the regime’s political opponents.

Though Mengistu effected a nominal transition to civilian government in 1987, he resolutely held on to power until the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) forced him into exile in 1991. Meles Zanawi clinched the leadership of this coalition of four organizations as the “the first among equals”. Over the years, as chief of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), he turned the EPRDF into a clique that concentrated powers in the hands of the TPLF, other Tigrayan power-brokers, and some elites of other ethnic groups. The Oromo have long been subject to the hegemony of the Amhara and the Tigrayans, but Zanawi was deft in instrumentalizing his coalition partner, the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation, in plundering the natural resources of Oromia. Historical memory of real or imagined grievances is always a potent force, and some Tigrayans surely remember that Haile Selassie, who on his father’s side was Amharic, invited the British Royal Air Force to bomb the Tigray province to quell the Woyane Rebellion in 1943. The Emperor is also said to have done nothing to aid the Tigrayans during the famine of 1958, when 100,000 of them perished. So, from the Tigrayan standpoint, if the Amhara were now being blindsided by the TPLF, they were surely only getting their comeuppance.

In 2012, Zanawi passed away but, contrary to common expectations, there was no succession struggle as such. Haile Mariam Desalegn, who had served as the Deputy Prime Minister, stepped into Zanawi’s shoes. He appeared acceptable to all—if only because he was unassuming and ethnically a Wolayta, a yet smaller ethnic group that accounts for 2.3% of the population. However, Desalegn found himself unable to contain the Oromo-led protests that swelled over the few years of his rule, and he resigned in February 2018. His place was taken by Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo who earned his stripes as a politician who fought aggressively for the economic and social rights of the Oromo and played a pivotal role in the resistance to land-grabbing in Oromia. His swift rise to the apex of Ethiopian politics was heralded as the dawn of a new era in the country’s fractured politics and he appeared to have fulfilled initial promises of peace and development by freeing political prisoners, encouraging opposition leaders to return from exile, and brokering peace deals in Eritrea and South Sudan. His work in ending the long territorial stalemate between Ethiopia and Eritrea even earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019.

However, within Ethiopia, opinion against him was turning, more particularly in Tigray in the north of Ethiopia where Abiy was seen as having launched a campaign of vilification and persecution of veteran Tigrayan politicians, bureaucrats, and military officers. By some accounts, the Tigrayans, who have a reputation as the country’s preeminent warriors, occupy about 60% of the senior military positions in the country’s armed forces. Abiy has pledged to bring that number down to 25%. The Tigrayans are not the only ones complaining. International NGOs complained that the press was being muzzled, and that, as in Kashmir, the state was resorting to frequent and massive internet shutdowns. Even among Abiy’s fellow Oromos, there was growing disaffection with his tendency to concentrate power into his own hands. Some see in Abiy yet another manifestation of the “Big Man” syndrome which is said to haunt African politics. The Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa, who has sung of the plight of his people, was assassinated in July 2020, and Jawar Mohammed, another Oromo politician seen as Abiy’s most potent foe, was hauled into jail on charges of terrorism.

If a storm was brewing, the pandemic may have brought it on. General elections had been scheduled for August but Abiy postponed them, citing the pandemic as a deterrent. Nevertheless, Tigray, in open defiance of the federal government, held elections in September and soon thereafter federal lawmakers moved to cut funding to the region. Tigrayan political leaders decided to revolt, and on November 4 Abiy started an offensive against Tigray with the claim that the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) had launched an attack on a military base, and on November 29 the Ethiopian military declared that it had taken possession of Mekele, the Tigray capital. The rebels claim the conflict is far from over.

To understand how Ethiopia has been brought to the present state of affairs, one must also turn to a feature of the Ethiopian Constitution of 1994 that alone makes the country rather distinct. Article 39.1 of the Constitution states that “every Nation, Nationality, and People in Ethiopia has an unconditional right to self-determination, including the right to secession.” Section 4 of the article stipulates how such secession might be effected, for example through a referendum. The federal government deemed the election “illegitimate”, and though secession was not on the referendum, the TPLF might quite plausibly claim that an election held in defiance of the federal government was implicitly a referendum on Tigray’s right to secede—a right recognized by 98.2% of the voters who supported the TPLF.

It is remarkable, of course, that the constitution of a “Federal Democratic Republic” should have provision for secession. This is perhaps all the more extraordinary in that the Ethiopian government recognizes that foreign states may seek to exploit its immense ethnic diversity. In late 2002, for instance, the government produced a lengthy report on the policy and strategy to be pursed with respect to foreign affairs and national security and noted that “some time ago the Siad Barre regime in Somalia launched an attack on Ethiopia on the presumption that Ethiopia was unable to offer a united resistance and that it would break up under military pressure. The regime in Eritrea (the shabia) similarly launched an aggression against Ethiopia thinking along the same lines.”

Even states with much longer histories of commitment to a federal structure, reasonably well-protected traditions of civil rights, and established protocols of electoral politics have not been bold enough to test the limits of federalism in this fashion. Yet, as the continuing political turmoil in Ethiopia clearly shows, it will take more than audacity in drawing up a constitution to honor the rights of peoples in a highly pluralistic state. Though Abiy is mentioned as a Oromo political figure, he was raised by his Amhara mother. Indeed, such dual, often triple, ancestry is far from being uncommon in Ethiopia; it may even be the unacknowledged norm, an open secret. The Emperor Haile Selassie, whose rule is viewed as having extended the Amhara hegemony that commenced with Menelik, the Emperor of Ethiopia (1899-1913) who is credited with birthing the modern empire-state and under whose reign Addis Ababa came to acquire the prominence it has since then occupied as the nation’s capital, had Oromo ancestry from his mother’s side. There are comparatively few people in Ethiopia who are “pure” Oromo, Amhara, Somali, Tigrayan, or whatever; but it may be precisely for this reason that the impulse to exorcise the other within oneself becomes irresistible, particularly as a political project.

One of the most characteristic features of our times is that ethnic identities have hardened rather than diminished in most countries. As the Rwandan genocide of 1994 showed, conflict—in this case along ethnic lines, though the divide could easily revolve around religion, linguistic affiliation, race, or some other trait ascribed to a group—is all the more pronounced and bitter when the parties to the conflict are closely related to each other, whether by “blood”, custom, or history. Sigmund Freud termed this phenomenon “the narcissism of minor differences”: the most minute differences are blown up and the Other is deemed intolerable, sometimes deserving of extermination. There is a tendency to dismiss conflicts such as the present one in Ethiopia as a problem peculiar to Africa, or as a troubled feature of evidently “failed states”, but Freud correctly saw this as a problem for modern civilization. Thus the present conflict in Ethiopia should be watched by all those who wonder about the future of multiethnic and pluralistic countries.

A different version of this article, which suggests why Ethiopia should be of particular interest to Indians, and offers a capsule account of the links between the two countries, was published under the same title on December 1 at abplive.in, here.

Translated into Polish by Marek Murawski and available here: http://fsu-university.com/secesja-w-etiopii-pluralizm-w-nowoczesnym-panstwie-narodowym/

One day the peoples of Africa will be free. Ethiopia.

LikeLike

As I was reading this, all I could think about it my head is how similar it was to the Rwandan Genocide, and then you brought it up. I love the quote by Freud about the “narcissism of minor differences,” which could realistically be applied to so many nations in the matter of civil wars. It is sad that so many African countries have to undergo such awful treatment in order to attain higher standards of living and thus freedom, which relates to the current issue in Nigeria of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad. I admit, when I first heard about SARS in Nigeria, I, stupidly, thought they were referencing the virus, as I believe the SARS virus is known as SARS-CoV and Coronovirus is SARS-coV-2. However, when I did some research, seeing the awful videos of the anti-robbery squad murdering massive amounts of peaceful, non-violent protestors, it really hurt my heart.

LikeLike

This was a great read for me since it helped me understand the struggles between the multiethnic factions within Ethiopia which has been amazing for me in my efforts to grasp the long and often complicated history between the various groups and people in the same geographical location. I was shocked to realize how dysfunctional the relations between the three major groups which include the Oromo, Amhara, and Tigray. These ethnic groups are often presented with revolts and large political protests that appear to never end. I thought that what President Abiy was accomplishing through the peaceful negotiations with neighboring countries was a step in the right direction through resolving some of the animosity between different groups, in which he could focus later on; however, the fact that he is Oromo seems to have played a significant role in his image remaining negative in the eyes of those who have been affected by his affiliated ethnic group. I don’t know how there will be any kind of unity between all the different ethnic groups within Ethiopia unless they can put aside their hatred for one another that’s mainly based on past affliction since it seems apparent to me that no matter who assumes leadership position they will be rejected simply because of their affiliation to a particular ethnic group.

LikeLike

This article truly helped me understand the hardship and struggle that Ethiopia is going through both as a country and as the major entities: the Amhara, Oromo, Tigray, and Somali. I have studied the Rwandan genocide specifically a lot in the past and the events that can occur in a civil war are truly terrible. Seen from the map, it seems like each major ethnic group occupies a certain area of Ethiopia, which reminds me a lot of the Tutsi’s and Hutu’s. I truly hope the different groups of Ethiopia can come together as a whole and set aside their differences. I see that civil wars often occur more in third world countries than second or first. If their economy and country were to develop into a second or even a first would country, I wonder to what extent this would affect the conflict between ethnic groups?

LikeLike