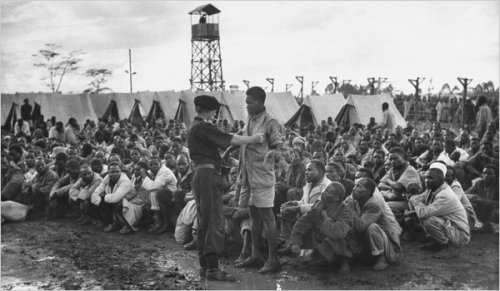

British policemen stand guard over a group of villagers while looking for Mau Mau rebels. Photograph: Popperfoto/Popperfoto/Getty Images

The ruling by a high court in London two weeks ago allowing three veterans of the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s to sue the British government for damages for torture is quite likely the most significant admission in recent years that British colonialism was far from being the gentleman’s form of oppression that it is often made out to be. One of the many idioms in which the great game of colonialism survives today is in those numerous discussions that seek to distinguish between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ colonialisms, between the barbaric Germans or King Leopold’s Belgian officials in the Congo and, on the other hand, those colonialists who allegedly brought the fruits of European enlightenment to underdeveloped people. It has long been held by some apologists of empire that the British were jolly good fellows: they may have committed excesses every now and then, but the country that gave the world cricket, a gentleman’s game complete with half-sleeved sweaters, finger sandwiches, tea, and, in the version that reigned supreme until relatively recent times, the likelihood of a drawn result after five days of genteel competition, cannot have bred mass murderers or genocidal fiends. On a state visit to east Africa in 2005, then Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown candidly declared: “I’ve talked to many people on my visit to Africa and the days of Britain having to apologise for its colonial history are over. We should celebrate much of our past rather than apologise for it” (Daily Mail, 15 January 2005).

The British repression of the Mau Mau rebellion forms one of the more gory chapters of violence in a century filled with brutality. The subjugation of Kenya commenced in the late 19th century when the European powers carved up Africa amongst themselves. British interest in Kenya was mainly strategic, and a railroad line was built in 1901 from Mombasa on the Indian Ocean coast to Lake Victoria in Kenya’s interior to facilitate access to the source of the Nile. The settlers who arrived immediately thereafter were offered farmlands in the Central Highlands at nominal prices. The indigenous Kikuyu were driven off the land, forced into reserves, and subjected to a draconian regime of taxation. Those outside the reserves became squatters on white-owned plantations and labored as virtually serfs.

Over the next few decades, following a long established British policy of developing a creamy layer of native elites who would serve the empire faithfully as collaborators, a small number of Kikuyu were also drawn into schools run by Christian churches. By the late 1930s, a movement of resistance had built up on several fronts, one among squatters whose pauperization had become unbearable and, secondly, among radical intellectuals centered in Nairobi. Moreover, though over 75,000 Kikuyus served the British empire during World War II, the veterans who returned home found themselves barely acknowledged and became part of a drifting and embittered slum population.

The economic and political conditions at the end of the war were thus ripe for a full-blown rebellion against British rule. Anti-colonial movements were sweeping Asia and the example of Indian independence, achieved in 1947, was paramount. By 1950, Kikuyu political formation would converge around three blocks, among them the militant nationalists who invoked the critical issue of landlessness and were thus able to forge ties of resistance among the working class, peasants, trade unionists, and the urban proletariat. When, in October 1952, a prominent loyalist, the term used to characterize those wealthy conservatives, usually Kikuyu chiefs, prominent landowners, businessmen, and churchmen who had thrown in their lot with the white settlers and the colonial regime, was assassinated in broad daylight, Governor Evelyn Baring imposed a State of Emergency.

The four years of the Mau Mau insurgency, which ended with the decimation of the rebel forces in late 1956, furnish a grim history of the naked violence of the colonial state. One part of the British campaign against the Mau Mau rebellion was directed against the rebels who fought from the cover of the forest, another against the larger civilian population that was thought to have taken the Mau Mau oath and provided the insurgents with food, shelter, and moral succor. Though a vast system of “detention camps” was set up to contain the rebels and their supporters, the British achieved something much more sinister, indeed something quite without parallel in history. Unlike the Nazis, who deported Jews to concentration camps, the British struck on the expedient of transforming extant Kikuyu villages into “emergency villages”, each of them complete with barbed wire, trenches, watch towers, and armed patrols. Nearly the entire Kikuyu population of 1.5 million was rendered suspect and thus placed in “detention”, and it is the civilian population that had to bear the greater burden of a war allegedly fought against insurgents. This was scarcely the first time that an oppressor failed to make a distinction between civilians and insurgents, but the concept of “emergency villages” puts a whole new complexion on our understanding of the history of concentration camps. Of course, no such narrative is without its complexities: the rebellion pitted insurgents not only against the colonial state, but as much against the “Home Guard”, comprised of Kikuyu “loyalists” who feared a change of regime.

Much of this history has been written about previously, but the quest for justice by a group of Mau Mau veterans –– Wambuga Wa Nyingi, Jane Muthoni Mara and Paulo Muoka Nzili –– who alleged torture at the hands of the colonial state’s functionaries led earlier this year to a previously undisclosed archive of documents that provides bone-chilling details of the suppression of the insurgency. One is not surprised that knives, broken bottles, and rifle barrels were inserted into women’s vaginas, or that Kikuyu men were anally raped. Some details, such as the account of a man roasted to death, are gruesome. Those who are familiar with the wretched history of British colonialism will not be surprised by some of the other matters recently brought to light, such as the fact that ministers in London were fully aware of the murder and torture being waged in the name of empire. The perpetrators of the worst atrocities were given full legal immunity. There is a warning in all this, though not the one drawn by counter-insurgency experts such as John Arquilla of the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, who in September 2003 wrote apropos of the British strategy of setting up Kikuyu “pseudo gangs” against the Mau Mau: “What worked in Kenya a half-century ago has a wonderful chance of undermining trust and recruitment among today’s terror networks.” The United States, which has in many respects become the successor imperial state, should not delude itself into thinking that it can emerge from its own military adventures without a similarly heavy toll on its own psyche and culture.

— A slightly abridged version has been published as “Jolly Good Fellows”, Times of India – Crest Edition (27 October 2012), p. 14.