The Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, sandwiched between Tibet and India, rarely obtrudes upon one’s consciousness. It is commonly described in the West as ‘fiercely protective of its traditions’, which is another way of saying that it has, thankfully, been resistant to the idea that it should, as the neo-liberals are fond of saying, “open up” to the West if it wishes to be more than just a footnote to history. Over the last decade, Bhutan has nonetheless splashed its way into the Western media every now and then for a very different reason, as the progenitor of the idea that Gross National Happiness should replace GNP (Gross National Product) as a more reliable indicator of a country’s well-doing. The young king of Bhutan has been one of the idea’s most enthusiastic advocates and it has not been without its takers, most particularly among those who have worked on ‘development’ and ‘social justice’ issues and are cognizant of the fact that the well-being of a nation and its people cannot be reduced to something called the GNP and a few other economic (or allied) determinants. Whatever the difficulties of ‘Gross National Happiness’, and they are considerable, the idea should perhaps be embraced for no other reason that it might put a few economists, the vastly overrated and frequently insolent practitioners of the dismal science, out of work. Happy is the country that has little or no need for economists.

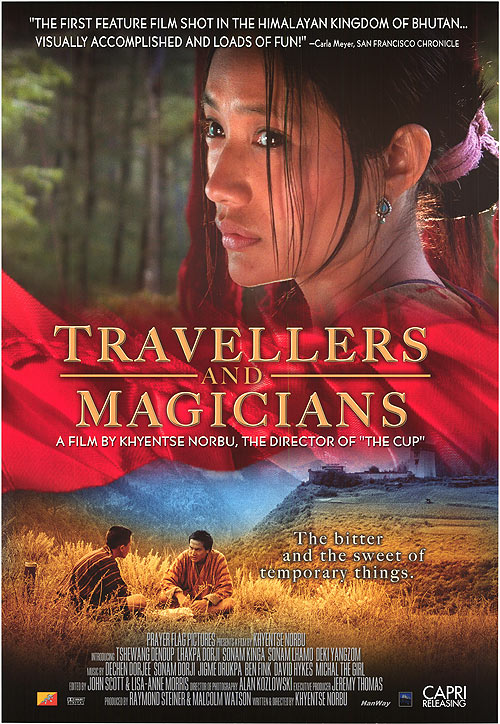

It may be too much to say that Bhutan, for all its remoteness, has a film industry; nevertheless, a few films have come out of Bhutan over the last several years. A few days ago, by happenstance, I came upon the first feature film out of Bhutan, and was struck, as surely every viewer would have been, by the charm, depth, and relative sophistication of Travelers and Magicians, “Chang Hup The Gi Tril Nung”, especially in the absence of a filmmaking tradition. Made in 2003 by Khyentse Norbu, the film is remarkable for more than its unhurried pace: much like Bhutan itself, the film steers refreshingly clear of the loud and mindless chatter of much of nearby Bollywood and Hollywood. Its central character, Dondup (Tshewang Dendup), a young official working in a village somewhere in central Bhutan, is in a hurry to get to Thimpu, the country’s capital: he has received a summons to a visa interview at the American Embassy. But why should anyone be in a hurry in Bhutan? If a young man in Bhutan is in a hurry, something is askance. When “the land of dreams” beckons, what else remains?

America’s reach is everywhere; the dream-work of America is happening in the remotest corners of the world. Dondup is what, borrowing the vocabulary from neighboring India, I would like to describe as the Resident Non-Bhutanese: though he lives in Bhutan, he might as well be living in America. Dondup has already been transported to America: he wears tennis sneakers, and, on more than one occasion, the camera lingers on these would-be Air Jordans, the vehicles of his carriage from one land to another. The walls of Dondup’s room are plastered with posters of white, sultry-looking girls; a large US army poster, “Uncle Sam Wants You”, with the familiar call to a glorious career in the mightiest military machine of the day, dominates one corner of the wall. American rock music blares from Dondup’s boom box; even the distinctly un-American Gho, a knee-length robe tied at the waist, which serves as Bhutan’s mandated national dress for men, is given a Yankee twist as Dondup sports a denim variety.

Dondup’s village is a two-day bus ride from Thimpu. He just misses the only bus of the day and tries to hitch a ride. As he waits by the roadside, he is joined by a peasant carrying a large sack of apples; a vehicle pulls up, but the driver assumes the two men are traveling together and says he cannot take them both. Down the winding mountain road comes, a short while later, a dramyin-strumming Buddhist monk (Sonam Kinga); before too long, a rice paper merchant and his pretty daughter, Sonam (Sonam Lhamo), have joined the party. The journey has long been a metaphor, in world literature and cinema, for self-discovery; but this voyaging into the self entails a twin-pronged movement, both into interiority and away from the crowd into the company of strangers. Thus, though Dondup starts out as the solitary traveler, the size of the party grows—but only so much, indeed just enough to prod him into some degree of anxiety and discomfort, then a modicum of self-reflection, and finally a recognition that the self seeks the other. The five pilgrims journeying into Thimpu are eventually picked up by a truck driver; as they clamber into the back, they discover they have a drunk for company. The drunk may not exemplify a higher consciousness, but he does point to altered states of consciousness. Much like the Buddhist monk, he remains unruffled: merry is he who is drunk—drunk on the love of God, or perhaps drunk in the lover’s embrace. Along a major turn-off, the five step down and the truck moves on.

Dondup, the young man in a hurry who seeks to leave for America, and the apple seller.

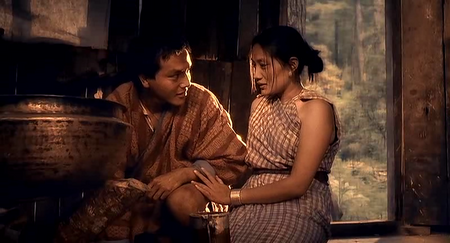

The narrative frame of Travelers and Magicians involves yet another element that has long informed Indian story-telling traditions. The road ahead is a long one; to pass the time, and prompted by Dondup’s desire to flee the apparently suffocating confines of village life in a hermit kingdom, the Buddhist monk takes it upon himself to share with Dondup and the others the story of Tashi (Lakhpa Dhorji), a villager who yearned to escape from the drudgery of everyday life. One might fault the film for occasionally taking recourse to a stock of clichés: thus, Tashi mounts what else but a white horse that he cannot tame. He is thrown to the ground and injures his leg; wandering around in a daze, Tashi is hopelessly lost in the remote mountains before he comes upon the home of an old woodcutter, Agay, married to a beautiful woman much younger to him. The old man rules over his young wife, Deki (Deki Yangzom), like a tyrant; she longs for a younger man’s touch and company, and Tashi and Deki are soon caught in a web of lust and jealousy. A plot is hatched; the old man’s chhang (liquor) is poisoned, but he seems to take a very long time to die, writhing and groaning in pain. This adulterous relationship ends as all such escapades do, as Deki falls to her death in the wild rapids as she pursues a fleeing Tashi.

Tashi and Deki caught in a web of lust and jealousy.

The story of Tashi is told not in one single take, but rather the film alternates between the main narrative frame and the interior frame; the filmmaker cuts seamlessly between the two stories, making effective use of dissolves, match cuts, and other cinematic devices. The interior story doesn’t exactly mirror the main framework story, which is what makes it all the more enticing; and yet there are enough elements—the desire to escape the constraints of village life, the voyaging forth into the unknown, the journey into the interior of one’s self, the entrapments of desire, the restlessness of the young—to stitch the two stories into a single narrative framework. The film is self-reflective about the art of story telling: stories are not to be told only to while away the time, but because stories, more other than forms of discourse, translate more easily from one culture into another. Was it Thucydides or Heraclitus who said that wherever one goes, one runs into a story?

The party disperses: the monk and Dondup finally a catch ride to Thimpu.

Travelers and Magicians deploys in many respects elements of a narrative structure with which we are familiar from other films and works of literature. Just as the party grew incrementally, so it diminishes incrementally. Some hours short of Thimpu, a bus finally pulls up before the party of five. Dondup, who had at the outset been in an extraordinary hurry to get to America, now seems rather indifferent to the land of dreams: the bus has room for only and he puts the apple-seller on it. And so the party of five has begun to scatter, the monk and Dondup taking a ride together into Thimpu. The destination is no longer of any consequence; the journey is everything. As Eliot put it hauntingly in “Little Gidding”,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Hey Vinay I remember seeing this film also indeed it nicely crossed the mythic with the charm of a folk tale yet as you point out what we miss on the journey might well be what is most important….after all…love, Appreciation of ordinary fellow travelers, etc

You might enjoy Soul Mountain by GAO the novel prize writer also a journey a search for a mountain in the hinterlands of southwest China.

Russell C. Leong 梁志英 http://www.mothsutra.com

>

LikeLike

Hi Russell, I’ve been meaning to read “Soul Mountain” for some time and have a copy in my library, but of books there is no end and “much study wearies the body” . . . (Ecclesiastes 12:12). Oh, yes, the journey is all, never better than when it is unhurried and assisted by a story. Cheers, Vinay

LikeLike