The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. whose birth anniversary is being celebrated today, was all of 39 years old when he was assassinated in 1968. Most political careers are far from having been established at that somewhat tender age: the man that had King had looked up to, Mohandas Gandhi, had made something of a name for himself when he was forty, but Gandhi was at that time still living in South Africa and no one could have anticipated that within a decade he would have been transformed into the leader of the Indian independence struggle. King was only in his late 20s when, perhaps somewhat fortuitously, the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1956 launched him onto the national stage; thereafter, his position as the preeminent face of the Civil Rights Movement was never in doubt. This is all the more surprising considering that King was scarcely stepping into a political vacuum: there was already a tradition of black political leadership and several of those who would become close associates of King had developed local and regional constituencies well before he arrived on the scene.

King has been the subject of several essays on this blog over the last few years. I have also had occasion to make reference to the extraordinary career of Reverend James M. Lawson, who initiated a nonviolent training workshop that would shape the careers of an entire generation of Civil Rights leaders such as John Lewis, Diane Nash, James Bevel, and many others. Rev. Lawson settled in Los Angeles in the early 1970s and was until a few years ago Pastor of the Holmes Methodist Church in the Adams district of Los Angeles. He remains firmly committed, at the age of 88, to the idea and practice of nonviolent resistance, and at the national level and particularly in the Los Angeles area his activism in the cause of social justice is, if I may use a cliché, the gold standard for aspiring activists. Over the last several years, over twelve lengthy meetings, we have conversed at length—26 hours on tape, to be precise—on the Civil Rights Movement, histories of nonviolent resistance, the Christian tradition of nonviolence, the state of black America, the notion of the Global South, and much else.

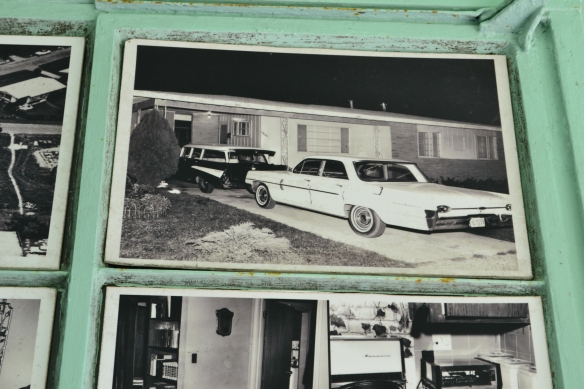

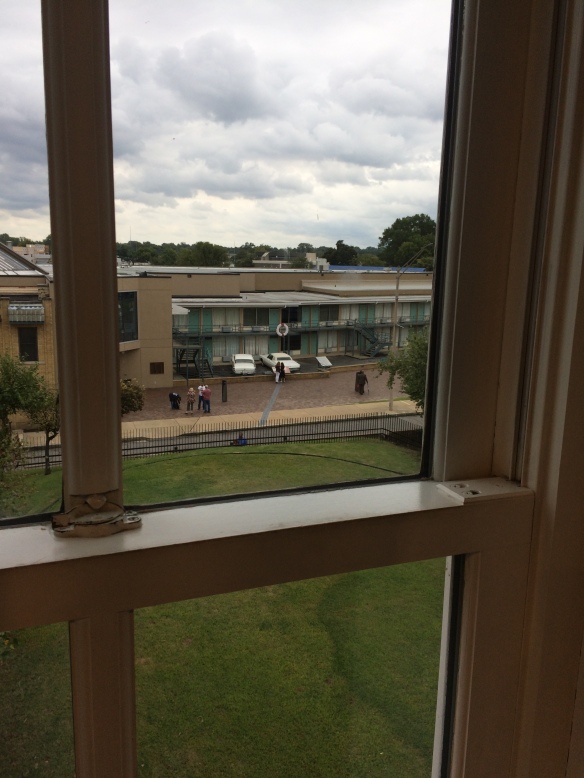

Rev. James Lawson discusses his phone call inviting Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis, the meeting at his church on April 3 and plans to go forward with a march with or without the court injunction in place. Copyright: Jeff McAdory/The Commercial Appeal. Source: http://www.commercialappeal.com/videos/news/2017/01/12/rev.-james-lawson-recalls-inviting-martin-luther-king-jr.-memphis/96495746/

What follows is a fragment, what I think is a remarkable piece, of one lengthy conversation, which took place on 31 January 2014, revolving around some of the difficulties that King encountered, the circumstances of his political ascendancy, the so-called “failure” of the Albany campaign, and the challenge posed to him by one white supremacist, the Sheriff of Albany, Laurie Pritchett. The fragment, which begins as it were mid-stream, has been only very lightly edited. I have neither annotated the conversation nor removed some of the rough edges.

Vinay: At this time, we’re talking about the Easter weekend 1960. I’ve read in various accounts that there was a bit of impatience with King on the part of a number of people; they thought he was not radical enough, he was too cautious.

Rev. Lawson: I think that’s reading into it.

Vinay: You think it’s reading into it?

Rev. Lawson: It’s also something else. Such a view does not understand how an organization espousing nonviolence comes into being.

Vinay: Can you say more?

Rev. Lawson: How the person who’s become the singular spokesperson in the country for Negroes.

Vinay: Was he at that time?

Rev. Lawson: Oh, absolutely.

Vinay: Already? In early 1960?

Rev. Lawson: Oh, yes.

Vinay: Undisputedly so.

Rev. Lawson: Undisputedly so. I watched it.

Vinay: Yeah.

Rev. Lawson: I saw some of the difficulties that he went through. He had a hard time because he was not supposed to become [the leader], he was not supposed to be. Traditional leadership in the Negro community, in the political community, did not anticipate a young man, 26 years of age, emerging at the head of an effective bus boycott that shakes the nation and the system and spreads around the world. He was not the chosen one. I watched this in ’58, ’59, ’60, ’61, ’62. The NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People] leadership said that mass action is not the way. They said it then.

Vinay: Yes.

Rev. Lawson: They said that legal action, clean up the constitution—that is the way. King actually as he emerged and saw what was happening with the bus boycott—he proposed to the NAACP a special direct action department of work. They rejected that idea, and said no to that.

It’s under that aegis, then, that King starts in ’57 meeting with other clergy and then organizes the Southern Christian Leadership Conference [SCLC]. Martin King had enough wisdom and humility that he wanted to add this dimension of life to the work of the NAACP, and the NAACP said very clearly no, that’s not possible. That’s excluded from these [academic] books. Worst of all, and excluded from these books, is the idea that a social campaign or movement is a social organism. It does not arrive fully structured, fully ideologically framed. It does not arrive with tactics in place.

Vinay: Yes, it’s a process.

Rev. Lawson: It’s a process. Especially it’s a process because all of the people who are attracted to it, I mean at least I my case I know, and Martin’s case I know, this was something brand new. We had not had any experience like that in our own limited backgrounds. I said boldly in ’59, I don’t know what I’m doing, but I’m doing it.

Vinay: I find your phrase “He was not the Chosen One” striking.

Rev. Lawson: Yeah.

Vinay: I think that perhaps it was fortuitous that Martin King was in Montgomery rather than in a place with traditional Black Leadership.

Rev. Lawson: In Atlanta.

Vinay: In Atlanta, because that would have been an obstruction.

Rev. Lawson: What these scholars have no inkling about is that when Martin in ’57 organizes the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with the help of Bayard Rustin and a number of other people, and creates SCLC; when he sets up and begins to set up the office in Atlanta, and knows that eventually he’s going to leave Montgomery and go to Atlanta to work, Martin King has made a commitment to himself. That commitment is, ‘I’m going back to Atlanta, I will be a co-pastor with my father, but I am not going to initiate any program in Atlanta.’

Why? Because Atlanta has an organized, traditional Black Leadership group who gather once a month maybe; business, churches and clergy, artists, presidents of colleges, and they talk about their situation together. They talk about every situation that’s coming up in Atlanta. His father is a member of that group. King knows that if he initiates something in Atlanta, he will have to deal with that traditional Black leadership and he does not want to. Julian Bond and Lonnie King, and John Mac, and Maryann Wright Edelman are people who are students in Atlanta at this time. They go to King to persuade King to take part in the sit-in campaign against riches [?] in downtown Atlanta. King is hesitant. He has probation problems legally, but that’s only one of them.

King’s major problem is that if he steps out in Atlanta, he will bypass Black traditional leadership. That will stir up the hornets in Atlanta. Now the students do not understand that. I’m not even sure that I recognized it at that time. I mean I discovered this in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but when I discover it, I’m pretty sure is ’60, ’61, ’62, ’63, not in those first months; these books don’t understand that.

King wants to be in the sit-in campaign, I have no doubt about that. Ralph Abernathy had no doubt about that. Others close to him had no about that. He would prefer to be with them without reservation, but he has to deal with the fact that when he does it, he’s got all the criticism in the Black traditional leadership who are already upset with this young whippersnapper who they helped to raise, who’s coming back to work in Atlanta, and will eclipse all of them.

Vinay: Yes, all of them, right.

Rev. Lawson: Now none of that is in these books.

Vinay: Yeah. Again, in many respects this story is rather similar [Lawson laughs, in anticipation] to you-know-who. Mohandas.

Rev. Lawson: Yes. Mohandas K.

Vinay: Gandhi, yes. Mohandas K.

Rev. Lawson: That’s right.

Vinay: He comes out of Ahmedabad; much of the political leadership is based in Bombay, Calcutta.

Rev. Lawson: Yeah.

Vinay: He’s able to in fact completely change the landscape.

Rev. Lawson: He comes to India and he is the best known Indian in India.

Vinay: Yeah.

Rev. Lawson: He hasn’t paid none of the price of living in India of the previous 15 years.

Vinay: Yup, and he hadn’t paid any of the dues as they would have said.

Rev. Lawson: Exactly, Exactly, and yet here he is. Exactly. You know that seems to be really the case when you have a social movement that’s going to set itself against the status quo of oppressions and tyrannies. It takes a different leadership in the first place to really do it, I think. In the second place that leadership immediately gets involved with the traditional leadership that’s been around. You create a whole new dynamic that’s not there before that.

Vinay: Let’s take apropos of this discussion, let’s take what is generally viewed, now your perspective might be different—that’s why I think it would be interesting to talk about it—let’s take the illustration of what is supposed to be one of Martin King’s more difficult moments. Still in the early ‘60s we are speaking about, and here I’m referring to what happens in Albany, Georgia. Now as you know very well the movement in Albany commences without King initially.

Rev. Lawson: Yeah, it’s locally started.

Vinay: Right yeah. It’s locally started, locally initiated.

Rev. Lawson: That’s right, it’s locally started.

Vinay: SNCC is not particularly keen on having King there, and he’s eventually invited by the local businessmen.

Rev. Lawson: By Anderson who is president of the movement in Albany. I can’t think of his first name, but he’s a doctor.

Vinay: Right.

Rev. Lawson: He’s a well-known doctor who is concerned for these changes and lends himself to it, and gets involved in helping make it happen.

Vinay: Right, so one perspective on what happened in Albany is the following. It’s been argued by a number of people; it’s also by the way shown in [the documentary] Eyes on the Prize; and is mentioned in quite a few of the scholarly works have delved into this. Generally, the view is that this was a failure for King, what happened in Albany. The perspective then generally amounts to the following.

Number one, that there King met, and the civil rights movement met, its’ match in Laurie Pritchett, who was the sheriff, I think, in Albany. Apparently, Pritchett had studied what had happened in India. In fact, this little clip in Eyes on the Prize, I was very surprised when I saw this clip where he’s interviewed, and he says I’m looking at what Gandhi did in India because that’s what these chaps are doing over here. This whole idea of filling up the jails, apparently what he did was he decided that he was going to spread out the prisoners across jails …

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is arrested by Albany’s Chief of Police, Laurie Pritchett, after praying at City Hall, on July 27, 1962. Source: AP Photo.

Rev. Lawson: Yes, I know the story.

Vinay: That Pritchett himself is now using the weapons of nonviolence as it were against the resistors themselves, right? That’s one part of the story. The other part of the story as I have encountered it, is that King comes in and that he misjudges the situation considerably. Ultimately, he has to sort of leave in defeat from Albany because the ultimate objectives of the movement were not met there. Now what is your perspective on what happened in Albany?

Albany Police Chief Laurie Pritchett & Martin Luther King, Jr. Source:

Rev. Lawson: Well, in the first place, I don’t think academics have the right to go and critique it when it is an emerging social process and organism, in which none of the people in Albany have done it before; they have limited experience; where the fledgling SCLC is still trying to organize its staff. It has an executive director who’s a good man, and a smart man, Wyatt T. Walker, but it’s still fledgling. When they yield to the invitation from the movement in Albany, and Dr. Anderson, they go in.

There are a handful of SNCC [Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] people who are operating in the area as well, who have helped to launch the movement themselves. How this takes place I think is greatly overlooked. One of the key figures in that business was Charles Gerard. Good man, still is a very good man, and Charles tells me, “Those who claim it was a failure don’t know what they’re talking about.” He said that boldly years ago to me.

King later of course says, in assessing it, that I had problems and SCLC had problems, but it was not a failure. Now the tensions that rose up among people is understandable. I don’t know them myself. King wants me to come there and I don’t go, but he doesn’t put any pressure on me to come.