Today, at 10 AM (California time), the Reverend James M. Lawson, one of the principal architects of the “civil rights movement”, and at the age of 92 an extraordinary fount of energy who remains a peerless example of the practitioner of nonviolence who leads by his moral example, and I–together with Dianne Dillon-Ridgley, a lifelong activist in human rights struggles–will be taking part in an hour-long panel discussion on “Gandhi, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Continuing Quest for Justice and Peace”. Rev. Lawson was last seen on the national stage just a few weeks ago, when he was called upon to speak at the funeral ceremonies for Representative John Lewis, a long-time Congressman from Georgia who was one of Lawson’s proteges in Nashville where the nonviolence training workshop was pioneered by Lawson. John Lewis, of course, went on to become a major figure in the movement, taking part in the freedom rides, becoming the head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and, perhaps most famously, marching alongside Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Selma. Rev. Lawson delivered a stirring funeral oration for John Lewis.

Tag Archives: Rev James M Lawson

*The Prison Cell and the Education of James M. Lawson

In an earlier essay about three weeks ago, I wrote in part on the increasing inability, as it seems to me, of people in our times to live with themselves and with their thoughts. Other commentators have spoken of this age as one of ‘instant gratification’, but I would underscore the word ‘instant’. Even ‘thoughts’ must be shared instantly. That essay was prompted by some reflections on the news that the British government had effectively appointed a “minister of loneliness”. Those who are not afflicted by cancer, diabetes, obesity, or a heart condition may nevertheless be overcome by loneliness. I distinguished between solitude, the virtues of which have been extolled by writers across generations and cultures, and loneliness—the latter a largely modern-day pathology. Loneliness is not singular either: there is the loneliness that one experiences when one arrives in a large city, knowing no one and feeling somewhat adrift; there is also the loneliness one sometimes feels amidst a very large crowd of people, even a crowd of well-wishers or fellow travelers; and then there is the loneliness in moments of intimacy. Perhaps some moments of loneliness are also critical for self-realization: it is, I suspect, only when loneliness becomes the norm that it starts to take on the characteristics of a pathology.

Solitude may perhaps be similarly parsed, but my subject at present is the prison cell and the education that the Reverend James M. Lawson, who turns 90 tomorrow, derived from his time after his first prison term following his arrest and conviction for resistance to the draft in 1950. I do not speak here of solitary confinement, which in the ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries alike is nothing but barbarism, but of the prison as a site of reflection, education, contemplation, quietude, as much as a site where revolutionaries have often been made. The movie industry, to the contrary, has largely feasted on the idea of the prison as a place where criminals are hardened, the will of political prisoners is broken, men are sodomized and women raped, and sadistic prison guards rule like little kings. In what follows, in two parts, I relay the conversation that transpired between Rev. Lawson and myself, first around Nelson Mandela and Robben Island, and then on the circumstances that led to Lawson’s own confinement to Mill Point Federal Prison in West Virginia. Our very first conversation took place a few days after the passing of Nelson Mandela in early December 2012; it has been only slightly edited:

Nelson Mandela, on his return to his cell at Robben Island in 1994, after being elected as the first President of a free South Africa. Photo: Jurgen Schadeberg/Getty Images.

VL: I just want to go back to Mandela for a moment. I think whatever one might say about Mandela and the founding of the Umkhonto we Sizwe [the armed wing of the African National Congress], and his decision to embrace violence alongside nonviolence—Mandela was very clear that nonviolence would not be given up entirely—so, whatever one might say about all of that, I think to most people the Mandela that comes to mind is the man who walked out of prison after an eternity in there. Those years in Robben Island—those become the heroic years. There are, very often, two kinds of outcomes when people have spent many years in jail, the better part of their lives behinds bars. One is, they come out really bitter. And, very often, we know that this has been one of the critiques of the prison system… I mean, other than the kind of argument, which I think you and I are familiar with, and we need not enter into at the present moment, and that’s about the so-called prison industrial complex, about the fact that the prison construction industry is one of the largest revenue earners for the state of California—the whole relationship between the prison complex and capitalism and so on… And I think that those are very important and interesting questions. But, here we are interested in the other outcome, something that may be seen from the life of Mandela. He came out of prison not just, in a manner of speaking, ‘intact’, however reservedly one might use that word; he came out of it, remarkably, with a more enhanced sense of the need for inclusiveness in a new South Africa.

JL: Stronger in his character and his visions…

VL: And I daresay this is where his generosity is most palpable… You know, the way in which he decides to handle certain problems, the way in which he decides to look at the whole issue of, well, what are we going to do with the Afrikaners now, what will be the place of white people in this society?… And this is where, as I said, his sense of inclusiveness is really very palpable. Much the same can be said for people like Gandhi, King, Nehru, and many others who spent [time in jail].

JL: Also, Castro.

VL: Castro… I hadn’t quite thought of him in this regard, but you may be right, when we think of the two years to which he was confined to jail by Bautista. But many people who served fairly long prison terms, they actually –in the case of Gandhi, I am quite certain of that because I’ve looked at his life in very great detail, I think that he almost welcomed prison terms because . . .

JL: He did.

VL: . . . it helped him to renew his sense of life, it energized him, it also gave him solitude; he was far from the maddening crowds, it gave him time for deep introspection and reflection. And I think that this is what happens in Mandela’s life, too. Now, here perhaps Mandela had far too much time for introspection, so to speak, because I have the distinct feeling that one of the things that happened is that Mandela really was no longer in contact with what was happening in the wider world outside; he no longer had the full pulse of the nation he would later have guide through the first flush of freedom.

JL: But, but, he turns Robben Island into what they called at one point the University.

VL: Absolutely.

JL: The prisoners, sharing what they did know, really engaged in long conversations about their situation, about their country, about their philosophy. And that, of course, he may have learned from Gandhi. I learned it from Gandhi. And that is very clear in Gandhi’s life. I’ll never forget the first time I was arrested in Nashville, in 1960. I was physically exhausted, though very intellectually and spiritually alive. And I welcomed the knowledge that the police issued a warrant for me. And we arranged for us to do it jointly. And I went to First Baptist Church, and I was arrested out of First Baptist Church; but I had an armful of books with me that my wife had brought to me from home, and she came to the church. And as I got arrested, there was a great sigh of relief, and I had these books… and when I hit the jail, my first impulse was, first of all, to sleep through the night, get up in the morning, and begin over with the books. And I’ve read that in Gandhi as well. I’ve read that about Gandhi on two or three occasions. He welcomed jail in the Champaran campaign. He came to the court ready to go to jail because he knew it was going to be a time for him to do reflection and the rest of it… rejuvenate himself there in the isolation that he would have.

Yerwada Central Jai, Pune, where Gandhi was confined more than once.

VL: And he’d had that experience already in South Africa.

JL: That’s right. Exactly.

VL: You’re right by the way about the prison yard at Robben Island being turned into a university. There’s an Indian sociologist in South Africa by the name of Ashwin Desai, a good friend of mine, who published a book very recently last year [2011], called “Reading Revolution: Shakespeare on Robben Island”.

JL: Oh, really! My goodness!

VL: And this whole book is really a study of how people like Mandela and Tambo and Ahmad Kathrada and many others, how they actually read Shakespeare and discussed Shakespeare and each person marked their favorite passage. Because, of course, to read Shakespeare is also to enter into discussions of ethics, political rebellions, and the whole idea of—we were talking about it earlier—assassinations, as an example. So, I think that what you are saying is absolutely on the mark. Nevertheless, I think there are some serious questions that have to be entertained, such as Mandela’s views on globalization–what did he really understand by globalization? Because I think, to some extent, Mandela was not sufficiently aware of the manner in which the world has changed in the long years that he was actually confined to prison. When you look at Mandela’s economic policies, what I would call something of a capitulation to free-market policies takes place rather quickly.

The Robben Island Shakespeare was wrapped in a cover with images of Hindu deities.

(to be continued)

*James M. Lawson: An American Architect of Nonviolent Resistance

The Reverend James M. Lawson of Los Angeles is quite likely the greatest living exponent of nonviolent resistance in the United States, and he turns a glorious 90 on September 22nd. This is as good a time as any to pay tribute to a person who has the distinction, though it has never been acknowledged as such, of having been a dedicated and rigorous practitioner of nonviolence for longer (nearly seven decades, by my reckoning) than anyone else in recorded American history.

Most scholarly histories of the American Civil Rights movement have recognized the distinct contribution of Rev. Lawson, presently Pastor Emeritus of the Holman United Methodist Church in Los Angeles’ Adams District, as one of the most influential architects of the movement. In his dense, indeed exhaustive, narrative of the Freedom Rides, Raymond Arsenault recounts how James Lawson, who commenced his nonviolent training workshops in the late 1950s, gathered what would become a stellar group of young African American men and women—Diane Nash, John Lewis, Bernard Lafayette, John Bevel, among others—around him in Nashville. Martin Luther King Jr. himself acknowledged Lawson’s Nashville group as “the best organized and most disciplined in the Southland,” and King and other activists were “dazzled” by Lawson’s “concrete visions of social justice and ‘the beloved community’” (Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, Oxford UP, 2006, p. 87).

Rev. Lawson (in sunglasses, front) with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King and others at the James Meredith March Against Fear, Mississippi.

Andrew Young similarly speaks of Lawson in glowing terms as the chief instigator of the sit-ins and “as an expert on Gandhian philosophy” who “was instrumental in organizing our Birmingham nonviolent protest workshops”; Lawson was, as Young avers, “an old friend of the movement” when, in 1968, he invited King to Memphis to speak in support of the sanitation workers’ strike (see An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America, HarperCollins Publishers, 1996). Most strikingly, the chapter on the campaign for civil rights in the American South in Peter Ackerman and Jack Duvall’s global history of nonviolent resistance, A Force More Powerful (St. Martin’s Press, 2000), is focused not on King, James Farmer, A. Philip Randolph, or Roy Wilkins, to mention four of those who have been styled among the “Big Six”, but rather unexpectedly revolves around the critical place of Lawson’s extraordinary nonviolence training workshops—most recently featured in the feature film, Lee Daniels’ The Butler—in giving rise to what became some of the most characteristic expressions of nonviolent resistance, among them the sit-ins, the freedom rides, and the strategy of packing jails with dissenters. Ackerman and Luvall echo the sentiments of Lafayette, who credited Lawson with creating “a nonviolent academy, equivalent to West Point”; they pointedly add that though Lawson was “a man of faith, he approached the tasks of nonviolent conflict like a man of science” (pp. 316-17).

A mug shot of Rev. James M. Lawson after he was arrested in Mississippi for his role in the Freedom Rides. Source: https://breachofpeace.com/blog/?p=18

It is no exaggeration to suggest that King derived much of his understanding of Gandhi from Bayard Rustin and Rev. Lawson, though most histories mention only Rustin in this regard. John D’Emilio’s exhaustive biography, Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin (New York: Free Press, 2003) affirms what has long been known about King, namely that he “knew nothing” about Gandhian nonviolence even as he was preparing to launch the Montgomery Bus Boycott. D’Emilio states that “Rustin’s Gandhian credentials were impeccable”, and it fell upon Rustin to initiate the process that would transform King “into the most illustrious American proponent of nonviolence in the twentieth century.” Though Rustin’s command over the Gandhian literature is scarcely in question, the more critical role of Lawson in bringing King to a critical awareness of the Gandhian philosophy of satyagraha, and more generally in inflecting Christian traditions of nonviolence with the teachings of Gandhi and other vectors of the Indian tradition, has been obscured.

Uniquely among the great figures of the Civil Rights Movement, as I noted in an essay penned last year, Lawson spent three formative years in his early twenties in central India. As a college student in the late 1940s, Lawson discovered Christian nonviolence, most emphatically in the person of A. J. Muste, who was dubbed “the No. 1 US Pacifist” by Time in 1939 and would go on to be at the helm of every major movement of resistance to war from the 1920s until the end of the Vietnam War. Lawson was a conscientious objector during the Korean War and spent over a year in jail; as Andrew Young remarks, “His stand on the Korean War was courageous and unusual in the African-American community” (An Easy Burden, p. 126). Lawson spoke to me about his year in jail at considerable length during the course of our fourteen meetings from 2013-16 during which we conversed for something like 26 hours, and in future essays I shall turn to some of these conversations. Following his release from jail, Lawson, who had trained as a Methodist Minister, left for India where for three years he served as an athletic coach at Hislop College, Nagpur, originally founded in 1883 as a Presbyterian school. He deepened his understanding of Gandhi and met at length with several of Gandhi’s key associates, including Vinoba Bhave. When he returned to the US in June 1956, Lawson uniquely embodied within himself two strands that would converge in the Civil Rights movement: Christian nonviolence and Gandhian satyagraha. Lawson was never in doubt that satyagraha was to be viewed as a highly systematic inquiry into, and practice of, nonviolent resistance.

Strangely, notwithstanding Reverend Lawson’s place in the Civil Rights Movement and American public life more generally, very little systematic work has been done on his life and, in particular, on his six decades of experience as a theoretician and practitioner of nonviolent resistance. It is worth recalling that Lawson was a student of Gandhian ideas and more generally of the literature of nonviolence several years before King’s ascent into public prominence; five decades after the assassination of King, he regularly conducts workshops on nonviolence . No American life, in this respect, is comparable to his.

I shall be writing on Rev. Lawson often, I hope, in the weeks ahead. Meanwhile, I offer him my warmest felicitations on his 90th birthday!

*************

For a translation into Russian of this article by Angelina Baeva, click here.

For previous essays on Rev. Lawson on this blog, see:

The Nashville Sit-ins:

*The Nashville Sit-Ins: The Workshop of Nonviolence in Jim Crow America

and “Martin Luther King and the Challenge of Nonviolence”:

*The Abrahamic Revelation and the Walls of Separation: A Few Thoughts on the “Resolution” of the Palestinian-Israel Conflict

Fourth and Concluding Part of “Dispossession, Despair, and Defiance: Seventy Years of Occupation in Palestine”

As I argued in the last part of this essay, there is no gainsaying the fact that anti-Semitism remains rife among most Arab communities—and indeed among Christians in many parts of the world, as the attacks on synagogues, which have increased since the time that Mr. Trump assumed high office, amply demonstrate. Nevertheless, it is equally the case that the charge of anti-Semitism has itself become a totalitarian form of stifling dissent and an attempt to enforce complete submissiveness to the ideology of Zionism. On the geopolitical plane, the leadership (as it is called) of the United States, has done nothing to bring about an amicable resolution, even as the United States is construed as the peace-broker between Israel and the Palestinians. Indeed, one might well ask if the United States is even remotely the right party to position itself as an arbiter, and not only for the all too obvious reason that its staunch and nakedly partisan support for Israel, punctuated only by a few homilies on the necessity of exercising restraint and Israel’s right to protect itself in the face of the gravest provocations, makes it unfit to insert itself into the conflict as a peacemaker. We have seen this all too often, most recently of course in the carnage let loose on the border last week as Israel celebrated the 70th anniversary of its founding and the Palestinians marked seventy years of the catastrophe that has befallen them: even as Israel was mowing down Palestinian youth and young men, most of them unarmed and some evidently shot in the back, the United States was applauding Israel for acting “with restraint”.

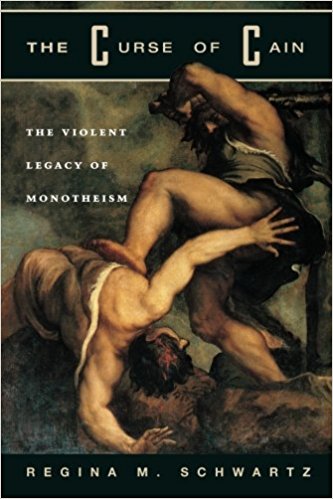

In an essay that Richard Falk wrote a few years ago at my invitation, entitled The Endless Search for a Just and Sustainable Peace: Palestine-Israel (2014), he advanced briefly an argument the implications of which, with respect to the conflict and its possible resolution, have never really been worked out. Falk observed that the Abrahamic revelation, from which the two political theologies that inform this conflict have taken their birth, is predisposed towards violence and even an annihilationist outlook towards the other. There is, in Regina M. Schwartz’s eloquently argued if little-known book, The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism (The University of Chicago Press, 1998), an extended treatment of this subject, though I suspect that her view that monotheistic religions have an intrinsic predisposition towards exterminationist violence will all too easily and with little thought be countered by those eager to demonstrate that religions guided by the Abrahamic revelation scarcely have a monopoly on violence. It has, for example, become a commonplace in certain strands of thinking in India to declare that nothing in the world equals the violence perpetrated in various idioms by upper-caste Hindus against lower-caste Hindus over the course of two millennia or more. One could, quite plausibly, also argue that there is a long-strand of nonviolent thinking available within the Christian dispensation, commencing with Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount and Paul’s injunctions towards nonviolent conduct in Romans and exemplified in our times by such dedicated practitioners of Christian nonviolence as A. J. Muste, Dorothy Day, the Berrigan Brothers, and the stalwarts of the Civil Rights Movement, among them the Reverends M. L. King, James M. Lawson, and Fred Shuttleworth.

Whatever one makes of the view that the political theologies that inform the Abrahamic revelation make a peaceful resolution of the Palestine-Israel conflict an immense challenge to the ethical imagination, what is perhaps being tacitly expressed here is a serious reservation about the fitness of the United States, which evangelicals would like to have openly recognized as a land of Abrahamic revelation, to intervene in this debate. I would put it rather more strongly. The supposition that the United States, which has all too often harbored genocidal feelings towards others, and has been consistently committed, through the change of administrations over the last few decades, to the idea that it must remain the paramount global power, can now act equitably and wisely in bringing a just peace to the region must be challenged at every turn. There is, as well, the equally profound question of whether there is anything within the national experience of the United States that allows it to consider such conflicts on a civilizational plane, not readily amenable to the nation-state framework and the rules that constitute normalized politics.Pa

Richard Falk sees, in the willingness of British government after decades of violence, arson, terrorist attacks, and a bitterness that surprised even those hardened by politics, to negotiate with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as a political entity some precedent for discussions that might lead to a framework for an equitable peace. Assuming this to be the case, one must nevertheless be aware that all proposed solutions to the conflict are fraught with acute hazards. Those who are inclined to see the conflict entirely or largely through the prism of religion have displayed little sensitivity to the idea that if religion repels frequently because of its exclusiveness it just as often attracts because of its potential inclusiveness. Those who look at the conflict entirely as a political matter will not concede what is palpably true, namely that the present practice of politics precludes possibilities of a just peace. The advocates of the two-state solution, clearly in an overwhelming majority today, must know that if such a solution becomes reality, Palestine will be little more than a Bantustan. Some may claim that even an impoverished, debilitated, and besieged but independent Palestine would be a better option for its subjects than the apartheid which circumscribes and demeans their lives today, but any such solution cannot be viewed as anything other than a surrender to the most debased notion of politics.

Israel should not be permitted to use the rantings of the Holocaust deniers, or the more severe anti-Semitic pronouncements of its detractors, as a foil for the equally implausible argument that the Palestinians are committed to the destruction of the Jewish state. The greater majority of the Palestinian leaders and intellectuals, as many commentators have points out, have signaled their acceptance of the pre-1967 borders of Israel provided that Israel withdraws from the territory it has occupied since the 1967 war and displays a serious willingness to address the refugee problem. In a more ideological vein, most Palestinians are reconciled to the idea that the Zionist project, originating in a desire to establish a Jewish state on Arab lands, is a fait accompli. However equitable a political solution—and that, too, seems to be a remote possibility—the more fundamental questions to which the conflict gives rise are those which touch upon our ability to live with others who are presented to us as radically different, even if the notion of the ‘radical’ that is at stake here is only grounded in historical contingencies. Living with others is never easy, and is not infrequently an unhappy, even traumatic, affair; but it is certainly the most challenging and humane way to check the impulse to gravitate towards outright discrimination, ethnic cleansing, and extermination. “We cannot choose”, Hannah Arendt has written, “with whom we cohabit the world”, but Israel appears to have signified its choice, terrifyingly so, not only by the erection of the Separation Wall, but also by imposing a draconian regime of segregationist measures that reek of apartheid. In so doing, it behooves Israel to recognize that victory is catastrophic for the vanquisher as much as defeat is catastrophic for the vanquished.

(concluded)

See also Part III, “Settlements, Judaization, and Anti-Semitism”

Part II, “A Vastly Unequal Struggle: Palestine, Israel, and the Disequilibrium of Power”

Part I, “Edward Said and an Exceptional Conflict”

For a Norwegian translation of this article by Lars Olden, see: http://prosciencescope.com/fjerde-og-avsluttende-delen-av-bortvising-fortvilelse-og-defiance-sytti-ar-med-okkupasjon-i-palestina/