On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Indian independence, August 15

In the wake of the “Har Ghar Tiranga” campaign, a campaign designed to encourage every Indian home (har ghar) to display the National Flag (tiranga, literally tri-colored), it is useful to think briefly about the evolution of the national flag, its place in the nationalist imagination during the anti-colonial struggle, and the particular way our relationship to the flag is a matter of the heart, the state, and the Indian constitution. Some people have thought that the orange in the flag represents the Hindu constituency, the green the Muslim community, and that all “others” are represented by the white in the flag. Gandhi had said as much, in an article for Young India on 13 April 1921, except that at that time red took the place of orange, but he also added that the charkha or spinning wheel in the middle of the flag pointed both to the oppressed condition of every Indian and simultaneously to the possibility of rejuvenating every household. The Constituent Assembly debates, which led to the adoption of the tricolored flag on 22 July 1947, suggest that some members were more inclined towards another interpretation, seeing the green as a symbol of nature and the fact that we are all children of ‘Mother Earth’, the orange as symbolizing renunciation and sacrifice, and white as symbolic of peace (shanti). That may be so, but the tiranga cannot be unraveled without some consideration of how it emerges from the three-forked road of the heart, the state, and the constitution.

Just what, however, is a national flag and why do all nation-states have one? The national anthem and the national flag are the bedrock of every nation-state; nearly all also have a national emblem, as does India. India has a complicated history around the national anthem, “Jana Gana Mana”, and the country officially also has a national song, “Vande Mataram”; and, then, there is an unofficial anthem, “Saare Jahan Se Accha”, which has wide currency. This makes the national flag especially and supremely important in India as an unambiguous marker of the nation-state. The honor and integrity of the nation are supposed to be captured by the flag, and the narrative of the nation-state everywhere offers ample testimony that the national flag is uniquely capable of enlisting the aid of citizens, giving rise to sentiments of nationalism, and evoking the supreme sacrifice of death. In a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and highly polyglot nation such as India, the national flag is there to remind every Indian that something unites them: before their allegiance to a language, religion, caste group, or anything else, they are Indian. Thus, in every respect, the national flag commands, not merely our respect, but our allegiance to the nation.

The Ministry of Culture’s “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav” website, of which the “Har Ghar Tiranga” campaign is one component, adds something quite different to the discussion. It states that “our relationship with the flag has always been more formal and institutional than personal”, and the campaign seeks to evoke in every Indian a “personal connection to the Tiranga” and “also an embodiment of our commitment to nation-building.” The idea, it says candidly, “is to invoke the feeling of patriotism.” To understand just what this means, we have to disentangle two elements: first, the question of patriotism; and, secondly, the fact that the relationship of Indians to the national flag is sought to be altered from a formal, stiff, and institutional relationship to a more personal and engaged one. Let us first turn to the second point, before returning to complete the broader discussion on patriotism.

Unlike countries such as the United States and Canada, India for a long time did not in fact permit ordinary citizens to fly the flag from their residence or business. This right was preserved as the prerogative of the state. “The Flag Code-India”, overhauled in 2002 and replaced by the “Flag Code of India”, and the Prevention of Insult to National Honour Act, 1971, set down the protocols to be observed in flying the national flag. In a now little-remembered but highly significant ruling on 21 September 1995, the Delhi High Court directed that the then “Flag Code-India” could not be interpreted so as to prevent an ordinary citizen from flying the National Flag from their business or residence. This eventually brought into existence the “Flag Code” of 2002, which permits unrestricted display of the tricolor consistent with the dignity and honor that is owed to the National Flag. However, aside from the question of the material to be used for making the National Flag, which has been the subject of considerable discussion in recent days, the Flag Code still imposed restrictions, such as being flown only “from sunrise to sunset “ (Para 2.2, sec. xi). The changes, moreover, were never public knowledge, and as a consequence it is safe to say that Indians have had a distant and formal, rather than personal and intimate, relationship to the National Flag. It is precisely this relationship that the “Har Ghar Tiranga” initiative has sought to change.

What is striking, and no longer seems to be a part of public or even institutional memory, is that in the two to three decades before independence, Indians did indeed have a personal relationship to the Congress flag or, as English officials with some derision described it, the Gandhi flag—the very flag that, after modifications, including the replacement of the charkha with Ashoka’s Lion Capital, would become the National Flag adopted by the Constituent Assembly. Congressmen and women fought government officials with zeal for the right to hoist their flag. They found that hoisting the flag invariably attracted the wrath, and often the vengeance, of British officials, and invariably ordered the flag to be brought down. On the rare occasion that a government official allowed the Congress flag to fly, he would receive an instant reprimand from the colonial government. This happened in 1923 in Bhagalpur, where the official consented to have the Congress flag flown alongside the Union Jack, albeit at a lower height. Not only the Government of India, but the British Cabinet issued a stern note saying “that in no circumstances should the Swaraj or Gandhi Flag be flown in conjunction with even below the Union Jack.” During the Salt Satyagraha, boys as young as eight years old were whipped for the offense of flying the flag or trying to hoist it. The indomitable Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, in her riveting memoirs, has described the tussle over the flag during the Salt Satyagraha, with the Congress Volunteers hoisting the flag time after time, and the police lowering it each time. “Up with the Flag”, “Up with the Flag”—the echoes kept ringing in her ears.

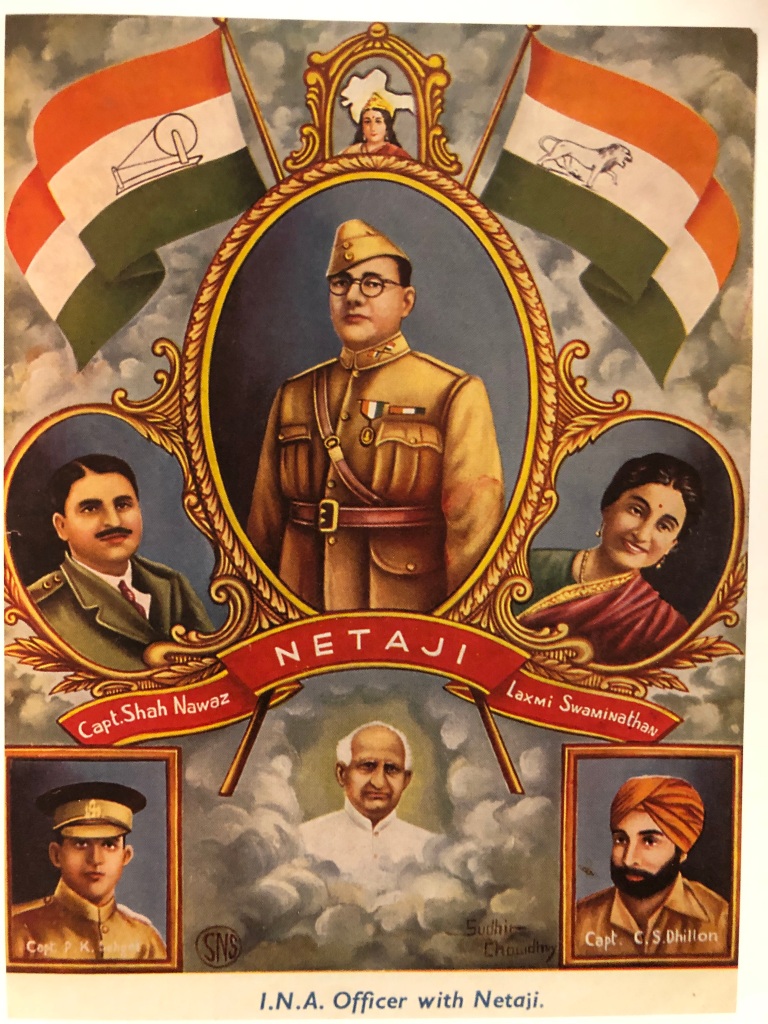

The right to fly the National Flag, in other words, was won after an arduous struggle. The flag evolved over time: it was Bhikaji Cama, who edited the newspaper Bande Mataram and closely networked with Indian revolutionaries in Europe, who unfurled the first Indian national flag at the 2nd Socialist International Congress at Stuttgart in 1907, and Kamaladevi rightly points out that she “installed India as a political entity” by doing so. The same flag had been hoisted for the first time in Calcutta in 1906. By 1921, the charkha had been installed at its center at Gandhi’s instigation, and the flag was again modified in 1931. As Gandhi had written, “a flag is a necessity for all nations. Millions have died for it. It is no doubt a kind of idolatry which it would be a sin to destroy.” Seeing how British hearts pounded with pride at seeing the Union Jack fluttering in the wind, Gandhi asked whether it was not similarly necessary that all Indians “recognize a common flag to live and to die for”? If the Congress flag accompanied every campaign, artists similarly positioned the flag prominently in their artwork. In a 1945 color print celebrating Subhas Bose and the heroes of the Indian National Army who were put on trial on charges of treason, we see the Congress flag with the charkha, and the INA flag with the springing tiger, on either side of Subhas Bose (see fig. 1). Martyrs fell along the way, but their struggle was not in vain: in Sudhir Chowdhury’s print from 1947, the heads of the martyrs, among them Bhagat Singh and Khudiram Bose, lie at the feet of Bharat Mata, who hands the tiranga to Nehru on the eve of independence (see fig. 2). In her various hands, she holds the other iterations of the national flag before it evolved into the tiranga.

If Indians fought for the national flag with zeal, they did so because they believed in what it stood for and they did so from their own volition against colonial oppression. The affection for the flag came from within, as a mandate from the heart rather than from the state. In any discussion of what the flag means today, it must be borne in mind that though the business of the state is to produce patriotic citizens, a patriotism that is manufactured by the state cannot endure and is as ephemeral as a market commodity. It is no less pertinent that the Constitution of India has nothing to say on the national flag. Though former Chief Justice Khare, heading a three-member bench of the Supreme Court, stated in 2004 that the citizen had a fundamental right to fly the flag as guaranteed by Article 19 (1)(a) of the Constitution, the article in question is about the freedom of speech and expression, and the right to fly the flag was interpreted as being subsumed by the larger right specified by Art. 19 (1)(a).

The Constitution has, of course, nothing to say explicitly on thousands of subjects, and Chief Justice Khare did what courts must do, namely interpret the Constitution. That is well and good, but we must confront the fact that many who honor the flag do not necessarily honor the Constitution. The state may be no exception; indeed, it is far likely to honor the flag rather than the constitution. A rogue can fly a flag as much as a saint; it takes almost nothing to show one’s patriotism. If patriotism can be purchased on the cheap, for a 5-rupee (7. 5 cents) plastic flag put together in China, which the present regime in India has derided as the mortal enemy, it is practically worthless. That larger right to freedom of speech and expression which subsumes the right to fly the flag is critically important, but it is also equally important to recognize that the Constitution, as the supreme law of the land, itself subsumes the National Flag. Now that the citizens of India have won the right to hoist the National Flag without restriction, consistent with respect to the National Flag, it is perhaps time to think about the corresponding duty they owe to respect the freedom of speech and expression, and the obligation, which the present government has shown little if any interest in honoring, to protect the Fundamental Rights promised in the Constitution to every citizen.

First published under the same title in a slightly shorter form at abplive.in, here.

Gujarati translation by abplive.in available, here.