As India prepares to celebrate the 75th anniversary of its independence on August 15th, attention will naturally gravitate towards those who were the principal architects of the movement that gave us azaadi. In the current mood, and under the present political dispensation, one can be certain that even though the putative “Father of the Nation”, Mahatma Gandhi, will be mentioned in the usual pious tones, many others will be celebrated as the greater architects of the freedom struggle. The marginalization of Gandhi has, of course, been going on for some time, indeed long before the present BJP government came into power, and the extraordinary success of the South Indian film “RRR” tells us something about the film culture of our days, the political sensibility of many Indians, and the manner in which the narrative of the freedom struggle is being rewritten. The film is a visual extravaganza that celebrates most of the “real warriors” who delivered India from the yoke of colonial rule, and it comes as no surprise that neither Gandhi nor Jawaharlal Nehru are deemed worthy of inclusion in the galaxy of heroes. Quite predictably, the film invokes, particularly towards the end, the legacies of Subhas Bose, Bhagat Singh, and Sardar Patel among others. The screenwriter of the film, Vijayendra Prasad, has gone on record as saying that online posts—from Instagram, Twitter, WhatsApp—from some friends made him question five years ago whether Gandhi and Nehru had done anything for the country, and he says he began to reject the orthodox historical narrative that was being taught in Indian schools when he was a child. When you learn your history from WhatsApp and Twitter, what you get is “RRR”—a visual spectacle, but absolutely brainless, and one that is curiously devoid of any understanding of the language of cinema. This is, of course, apart from the question of what the makers of the films understand by India’s adivasi culture, or their interpretation of caste and its political histories.

One way to comprehend what was transpiring during the freedom struggle and in its immediate aftermath is to understand how artists at that time responded to the events unfolding before them. A very small if sophisticated body of work has emerged around this subject, but what has been written on it—often in obtuse language—is largely for scholars, all the more ironical because much of the art of that time is ephemeral, more like bazaar art, and one would imagine that the scholars who have sought to rescue this work from oblivion are sensitive to the fact that bazaar art is after all for the bazaar, that is for common people. What becomes evident from a perusal of the art is that the artists and printmakers saw in Gandhi the supreme embodiment of the aspirations of a people striving to be free. They unhesitatingly turned Gandhi into the presiding deity of the political landscape. By far the greatest number of nationalist prints, as they may be called, feature him and the political events and the political theatre to which he gave birth—whether it be the Champaran Satyagraha, the noncooperation movement, the no-tax campaigns such as the Bardoli Satyagraha, the Salt Satyagraha, or the Quit India movement. What is even more extraordinary is that the printmakers and artists also unhesitatingly placed him, and him alone of all the political luminaries of that time, as akin to the founder of religions and as the true inheritor of the spiritual legacy of Indian civilization. Thus, for example, in the poster by P. S. Ramachandra Rao that appeared from Madras in 1947-48 entitled “The Splendour That is India”, Gandhi is placed in the pantheon of “great souls”—Valmiki, Thiruvalluvar, the Buddha, Mahavira, Shankaracharya, the philosopher Ramanuja, Guru Nanak, Ramakrishna, Ramana Maharishi—who are thought to have animated the spiritual life of a people (see fig. 1).

Let us turn, however, to some more modest prints that came out of a workshop in Kanpur established by Shyam Sundar Lal, who described himself as a “Picture Merchant” and set up a business at the chowk. It is not possible to go into the details of how Kanpur came to have such an important though not singular place in nationalist art, but it is useful to recall that Kanpur [or Cawnpore, as it was known to the British] was the site of critical events during the Rebellion of 1857-58. As a major manufacturing hub and production centre for supplies required by the army by the late 19th century, Kanpur also became important for labour union organizing and it was a city where communists and Congressmen both jostled for power. We do not know exactly how these prints were circulated, distributed, or used. Did they pass from hand to hand? Where they pasted on walls in public places or framed and displayed in homes? We do not even know how many copies were printed of each print, and indeed how many designs were in circulation for around the twenty to thirty years that the workshop was in business. But the prints that have survived make it possible to draw some inferences about how printmakers viewed the nationalist struggle.

One of the artists who produced prints diligently for Sundar Lal’s workshop was Prabhu Dayal and we may confine ourselves to three examples of his artwork. In a print entitled “Satyagraha Yoga-Sadhana”, or the achievement of satyagraha by the discipline of yoga, Gandhi is shown centre-stage, with Motilal Nehru and his son Jawaharlal positioned at either end of the Mahatma (see fig. 2). He sits meditatively on a bed of thorns, reminiscent perhaps of the dying Bhishma as he lay upon a sheaf of arrows and delivered a last set of teachings on the duties of the king and the slipperiness of dharma. There are no rose bushes without thorns; similarly, there is no freedom without restraint and discipline. The resolution for purna swaraj had been passed in December 1929 by the Congress at the annual meeting in Lahore presided over by Jawaharlal, and it is the rays of full independence or “poori azaadi” that shine upon the three.

More remarkable still is a print from 1930 which casts the epic battle between Rama and Ravana as a modern-day struggle between Gandhi and the British, between ahimsa (nonviolence) and himsa (violence), between satya (truth) and asatya (falsehood; see fig. 3). The ten-headed Ravana is incarnated as the hydra-headed machinery of death and oppression known as the British Raj. This struggle is represented as the Ramayana of our times. In this “struggle for freedom” (“swarajya ki larai”), Gandhi’s only weapons are the spindle and the charkha, though just as Rama was aided by Hanuman, so Gandhi is aided by Nehru. There is no mistaking the fact that Nehru is rendered as the modern-day Hanuman, who, in his hunt for the life-saving drug (sanjivini), carried back the mountain. A forlorn-looking Bharat Mata, Mother India, languishes in one corner of the print, cast in the shadow of the architecture of the new imperial capital built by the British as a monument to their own power. Gandhi in his rustic dhoti, bare-chested, presents a stark contrast to the Hun-looking British official in high boots whose hands bear a multitude of weapons of oppression: artillery, the baton of the police, military aircraft, indeed the entire arsenal of the armed forces and the navy. The oppressive and power-crazy British also wield Section 144 of the Indian Penal Code, which restricted the assembly of people and was used by the colonial state to foil nationalist demonstrations—and is still being used in independent India.

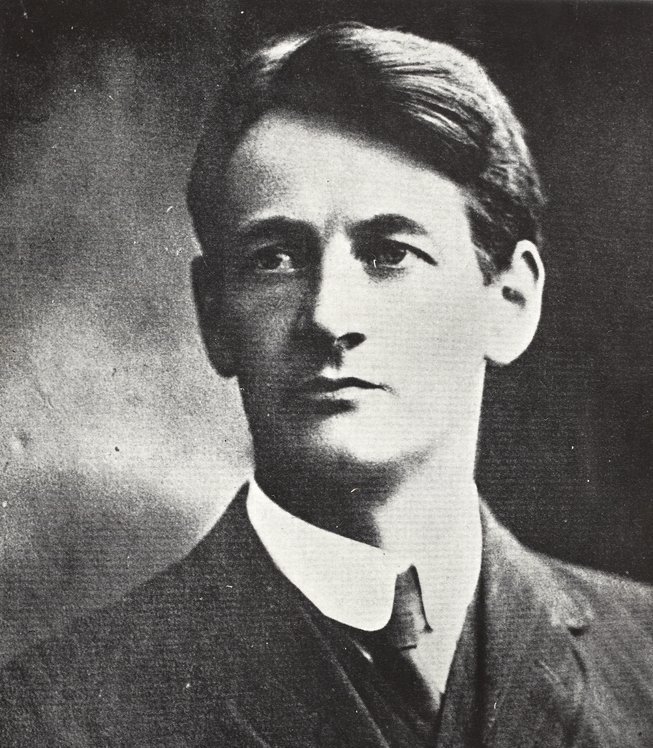

Prabhu Dayal, however, was ecumenical in his comprehension of the different strands of the freedom movement. Contrary to the view which some had then, and which is increasingly becoming popular among those who deride nonviolence and imagine that Gandhi was an effete individual who placed before his country a worldview for which a muscular nation-state can have no respect, Dayal did not see Bhagat Singh or Subhas Bose as having an antagonistic relationship to Mahatma. Much of his work suggests the complementariness between Gandhi and Bhagat Singh as in, for instance, this print entitled “Swatantrata ki Vedi par Viron ka Balidan”, or “The Sacrifice of Heroes at the Altar of Independence” (see fig. 4). Here Bhagat Singh, Motilal, Jawaharlal, Gandhi, and countless other Indians are lined up before Bharat Mata with the heads of the immortal martyrs, ‘amar shahid’, who have heroically already laid down their lives for the nation: Ashfaqullah [Khan], Rajendra Lahiri, Ramprasad Bismil, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Jatindranath Das. Prabhu Dayal did not doubt the sacrifice of the “Lion of the Punjab”, Lala Lajpat Rai, or of the many young men who took up arms in their quest for India’s independence.

Much of this artwork has only in recent years begun to receive the critical scrutiny of historians and other scholars. These prints do not only tell the story of the freedom movement; rather, they helped to forge the identity of the nation. What kind of art will do the same at this critical juncture of India’s history remains to be seen.

Note: All the prints are part of the author’s own collection. This article is related to, and in part drawn from, his forthcoming book, Insurgency and the Artist (New Delhi: Roli Books, c. Oct 2022).

This is a slightly revised version of a piece first published under the same title at abplive.in on 12 August 2022.

Published in a Marathi translation at ABP Network, here.

Also available in Bengali translation at bengali.abplive.in, here.

And in a Gujarati translation at gujarati.abplive.in, here.