It is on this day, August 9, seventy-seven years ago, that the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. Several air-raid alarms had sounded early that morning, but such warnings had by now become routine. The Americans had been firebombing Japanese cities for months, and there was little reason to suspect that this morning would be any different. Two B-29 Superfortresses, as the gigantic bombers were called, had left Tinian air base and arrived at Kokura, the intended target, at 9:50 AM, but the cloud cover was too thick to drop the bomb with any degree of accuracy and the planes departed for the secondary target, Nagasaki. Here, once again, visibility was sharply reduced owing to thick clouds, but then, fortuitously for the animated plane crew, the veil was lifted momentarily—just enough to drop “Fat Boy”, as the bomb was nicknamed, at 11:02 AM. Nagasaki had thus far not been laid to waste: a deliberate decision, since the effect of the bomb could not be judged if it were dropped on a city that had already been reduced to rubble. The clouds had parted, and the virginal city was now open to being ravished by “Fat Boy”.

At the moment of detonation, less than a minute later, something like 40,000 people were killed instantly. Over the next five to six months, another 30,000 died from their injuries; the casualties would continue to mount over the years, some succumbing to their injuries, others to the creeping radiation. At least 100,000 people had died within a few years in consequence of the bombing. Almost ninety percent of the buildings within a 2.5-kilometre radius of the hypocenter, or “ground zero”, were entirely destroyed. The following day, August 10, following the expressed wishes of the Emperor, the Japanese government conveyed its surrender to the Allied forces, though the American insistence on an “unconditional surrender” continued to be a stumbling block for several days. It was not until August 15 that Emperor Hirohito, taking to the airwaves to speak to his people directly for the first time, announced Japan’s surrender. On September 2nd, the Japanese foreign minister signed the instrument of surrender, and the hostilities of World War II were formally brought to a close.

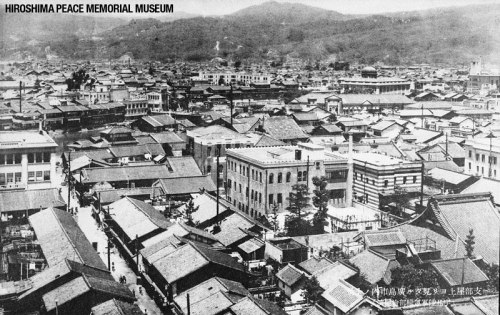

The atomic bombing of Nagasaki has been, comparatively speaking, little explored and it is similarly less recognized and commemorated than the bombing of Hiroshima three days earlier. It is, of course, the singular misfortune of Hiroshima that it ushered humanity into the nuclear age and catapulted humanity to new and heightened levels of barbarism. “Little Boy”, the bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, killed 70,000 people instantly—at the moment of detonation. The city was leveled, utterly ruined, and transformed into a mass graveyard. The graphic photographs that survive tell the same story, but in different idioms. There is the photograph of a young girl who survived initially but whose eyes were hollowed out; she was blinded by the bright light emitted by the explosion. Thousands of people were literally rendered naked: the intense heat and the fireballs stripped them of their clothes, and on one woman’s back the kimono’s pattern was seared into her flesh. This is one kind of barbarism.

It is another if related kind of barbarism to adopt the view, in the words of an American military officer at that time, that “the entire population of Japan is a proper military target.” Fewer than 250 people who were killed in Hiroshima were soldiers; the targets, in other words, were the elderly, women, and children, Japanese men of fighting age already having left the city to serve in the armed forces or auxiliary services. The hyper-realists have always adhered to the position that, whatever restraints on warfare international law might impose, and whatever the ethical sentiments that soft-headed people may have, war is a brutal business and that at times nothing is forbidden in the pursuit of victory. Historians generally encompass this view under the rubric of “total war”.

It is still another kind of barbarism, however, to continue to defend both the atomic bombings years and decades later, as many Americans especially do, on grounds that are at best specious. As late as 2015, seventy years after the bombings and considerable scholarship calling into question the conventional view, a Pew Research Center survey indicated that 56 percent Americans supported the atomic bombings and another 10 percent declared themselves undecided. Many arguments have been advanced in defense of the use of the bomb. Some commentators resort to what I have already described as the argument that, in conditions of “total war”, nothing is impermissible. Since such an argument often sounds crass and unforgiving, others prefer to speak of “military necessity”. The defense of the bombings often hinges around Japan’s obdurate refusal to surrender on the terms that Americans had every right to impose.

However, at rock bottom, there is but one fundamental claim on which the proponents of the bombings rest their case. It is the argument that the atomic bombings saved lives. We can all envision scenarios, so goes the argument, where one preserves lives by taking other lives. Had the bombs not been dropped, the Americans would have had to undertake a land invasion, and the battle of Iowa Jima had shown the Americans that the Japanese would be prepared to defend their country to the last man—and perhaps woman and child. Tens of thousands of American soldiers would have been killed. The somewhat more sensitive adherents of this view, mindful of the fact that Americans are not the only people fully deserving to be viewed as “human”, insist on reminding everyone that hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians would also have been killed. Thus, it is not only American, but also Japanese, lives that were saved when the United States decided to unleash destruction on a scale the like of which had never been seen in history.

President Truman’s remarks on August 11 unequivocally suggest that saving Japanese lives was certainly not on his mind—and neither was it on the minds of the military planners or even the scientists charged with bringing to fruition the Manhattan Project: “The only language they [the Japanese] seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true.” There is but no doubt that the Japanese had been entirely dehumanized. In prosecuting the war against Germany, the United States always made it clear that the Nazis, not ordinary Germans, were the enemy; however, no such distinction was observed in prosecuting the war against Japan. Military planners and most ordinary Americans alike saw themselves as being at war against the Japanese, not just against the Japanese leadership. The savage lampooning of, and racism against, the Japanese is to be found in countless number of cartoons, writings, and official documents, as well as in the expressly pronounced views of people in the highest positions in the American government and society. The Chairman of the US War Manpower Commission, Paul V. McNutt, said that he “favored the extermination of the Japanese in toto”, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s own son, Elliott, admitted to the Vice President that he supported continuation of the war against Japan “until we have destroyed about half of the civilian population.”

A case can be made that the United States, in undertaking the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, committed war crimes, even crimes against humanity, and engaged in state terrorism. Quite reasonably, we may expect that such a view will be aggressively countered, though the argument that the dehumanization of the Japanese—even if precipitated to some extent by Japan’s own wartime atrocities, some on a monumental scale—played a role in the bombings seems to be unimpeachably true. Those who seek to defend the bombings appear, moreover, to be unable to comprehend that the nuclear bombs were not simply bigger and far more lethal bombs, and that the bombings were not merely a more aggravated and ferocious form of the strategic bombing carried out first by the Luftwaffe and then the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the U.S. Air Force. The atomic bombings breached a frontier; they constituted a transgression on a cosmic scale, bringing forth in the most terrifying way before humankind the awareness that the will to destroy may yet triumph over the will to live. The sheer indifference to the idea of life, any life, on the planet suggests the deep amorality that underlies the logic of the atomic bombings. In this sense, we may say that the crime of Hiroshima is the primordial crime of our modern age.

Still, is it also possible to argue that the crime of Nagasaki was yet greater than the crime of Hiroshima? Why did the Americans have to drop a second bomb? Why could they not have waited a few more days for Japan to surrender? The defenders of the Nagasaki bombing argue that, since the Japanese had not surrendered immediately after the Hiroshima bombing, it was quite apparent to the Americans that they were determined to keep fighting on. The Japanese may have believed that the United States had only one bomb; some argue that surrender was not an option for the Japanese since the warrior culture was pervasive in their society and “Oriental culture” does not permit such an ignominious ending. On the other side, it has been argued that American military planners had a toy, and what use is a toy if it is not going to be put into play.

As I have argued, and many others have argued this long before me, the atomic bombings were never just intended to induce Japan to surrender. Before the war had even ended, the United States was already preparing for the next war, and that against a mortal enemy—the Soviet Union. Japan, at this time, was an entirely decimated power; it was, indeed, of comparatively little interest to the Americans. If this sounds implausible to some, consider that Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, the Director of the Manhattan Project, himself confessed that “there was never from about two weeks from the time that I took charge of this Project any illusion on my part but that Russia was our enemy, and the Project was conducted on that basis.” It was imperative to convey to Stalin that the United States would not be prepared to allow the Soviet Union to spread the poison of communism around the globe and seek world domination; as Secretary of State James Byrnes remarked, “The demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia with America’s military might.”

With Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States sought to deliver a one-two punch: knock out Japan and put the Soviet Union on notice that the United States was prepared to exercise its Manifest Destiny as the one indispensable country in the world. “Power corrupts,” John Dalberg-Acton [Lord Acton] famously pronounced; “absolute power corrupts absolutely”.

First published under the same title at abplive.in on 9 August 2022.

Available in a Marathi translation, here.

Available in a Tamil translation, here.

Available in a Telugu translation, here.