No one in India today remembers the name of Terence MacSwiney, but in his own day his name reverberated throughout the country. He was such a legend that, when the Bengali revolutionary Jatin Das, a key figure in the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army and a comrade of Bhagat Singh, died from a prolonged hunger-strike in September 1929, he was canonized as ‘India’s own Terence MacSwiney’.

Terence MacSwiney died this day, October 25th, in 1920. Ireland, in the common imagination, is a land of poetry, anguished lovers, political rebels, verdant greenery—and drunkards. All of this may be true; one can certainly spend far too many evenings in an Irish pub, downing a pint of Guinness or Harp. MacSwiney was a poet, playwright, pamphleteer, and a political revolutionary who got himself elected as Lord Mayor of Cork, in south-west Ireland, during the Irish War of Independence. Indian nationalists followed events in Ireland closely, for though people of Irish extraction may have played an outsized role in the brutalization of India during the British Raj, the Irish themselves were dehumanized by the English and waged a heroic anti-colonial resistance. In India, the Irish were called upon to suppress such resistance. One has only to call to mind Reginald Dyer, the perpetrator of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, who though born in Murree (now in Pakistan) was educated at Middleton College in County Cork and subsequently at Dublin’s Royal College of Surgeons, and Michael O’Dwyer, the Limerick-born Irishman who as Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab gave Dyer a free hand and even valorized the mass murder of Indians as a ‘military necessity’.

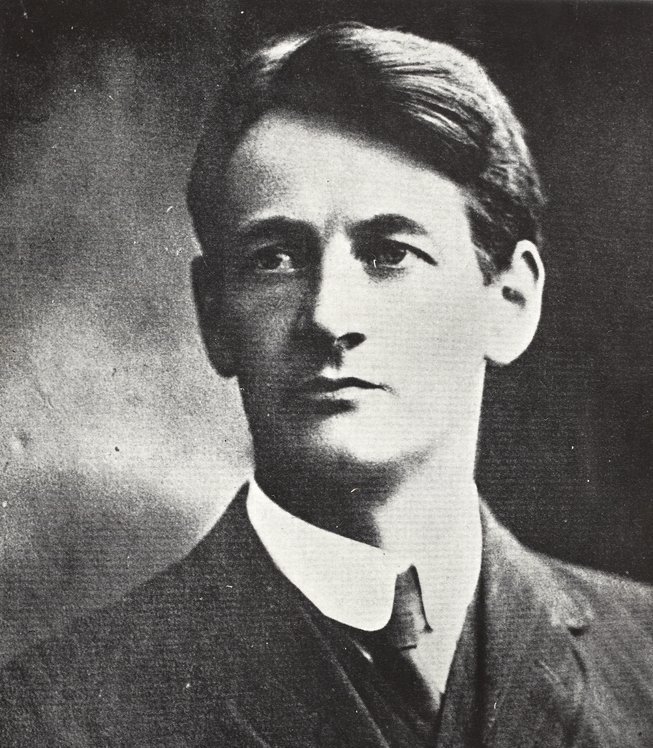

England did little in India that they had not previously done in Ireland, pauperizing the country and treating the Irish as a sub-human species. The Irish were ridiculed as gullible Catholics who gave their allegiance to the Pope. They were no better, from the English standpoint, than the superstitious Hindus. MacSwiney, born in 1879, came to political activism in his late 20s, and by 1913-14 he had assumed a position of some importance both in the Irish Volunteers, an organization founded ‘to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland’, and the Sinn Fein, a political party that advocated for the independence of the Irish. He was active during the ill-fated Easter Rebellion of April 1916, an armed insurrection that lasted all of six days before the British Army suppressed it with artillery and a massive military force. Much of Dublin was reduced to rubble. It is unlikely that the uprising would have disappeared into the mists of history, but in any case William Butler Yeats was there to immortalize ‘Easter 1916’: ‘All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.’ For the following four years, MacSwiney was in and out of British prisons, interned as a political detainee.

It is, however, the hunger-strike that MacSwiney undertook in August 1920 that would bring him to the attention of India and the rest of the world. He was arrested on August 12 on charges of being in possession of ‘seditious articles and documents’—an all too familiar scenario in present-day India—and was within days convicted by a court that sentenced him to a two-year sentence to be served out at Brixton Prison in England. MacSwiney declared before the tribunal, ‘I have decided the term of my imprisonment. Whatever your government may do, I shall be free, alive or dead, within a month.’ He at once started on a hunger-strike, protesting that the military court which had tried him had no jurisdiction over him, and eleven other Republican prisoners joined him. It was one thing for the large Irish diasporic population in the United States, whose predilection for Irish Republicanism was pronounced, to support him; but far more arresting was the fact that from Madrid to Rome, from Buenos Aires to New York and beyond to South Australia, the demand for MacSwiney’s release was voiced not only by the working class, but by political figures as different as Mussolini and the black nationalist Marcus Garvey. The days stretched on, and his supporters pleaded with him to give up his hunger-strike; meanwhile, in prison, the British attempted to force-feed him. On October 20, MacSwiney fell into a coma; seventy-four days into his hunger-strike, on October 25, he succumbed.

In India, MacSwiney’s travails had similarly taken the country by storm. It is assumed by many, as a matter of course, that Gandhi was greatly ‘influenced’ by MacSwiney, but though he was doubtless moved by his resolve, patriotism, and endurance, Gandhi distinguished between the ‘fast’ and the ‘hunger-strike’. Nevertheless, MacSwiney was a hero to armed revolutionaries—and to Jawaharlal Nehru. Writing some years after MacSwiney’s death to his daughter Indira, Nehru noted that the Irishman’s hunger-strike ‘thrilled Ireland’ and indeed the world: ‘When put in gaol he declared that he would come out, alive or dead, and gave up taking food. After he had fasted for seventy-five days his dead body was carried out of the gaol.’ It is unquestionably MacSwiney’s example, rather than that of Gandhi, that Bhagat Singh, Bhatukeshwar Dutt, and others implicated in the Lahore Conspiracy Case had in mind when in mid-1929 they commenced a hunger-strike to be recognized as ‘political prisoners’. That hunger-strike was joined by the Bengali political activist and bomb-maker, Jatindranath Das, in protest against the deplorable conditions in jail and in defence of the rights of political prisoners. Jatin died after 63 days on 13 September 1929. The nation grieved: as Nehru would record in his autobiography, ‘Jatin Das’s death created a sensation all over the country.’ Das would receive virtually a state funeral in Calcutta and Subhas Bose was among the pallbearers.

Though Gandhi was the master of the fast, the modern history of hunger-striking begins with Terence MacSwiney. It is quite likely that Gandhi recognized, more particularly after MacSwiney’s martyrdom, how the hunger-strike as a form of political theatre could galvanize not just a nation but world opinion. However, the life story of MacSwiney should resonate in India for many other reasons besides the singularity of MacSwiney’s admirable defence of the rights of his own people. As I have suggested, England under-developed Ireland before laying India to waste, and Ireland was in many respects as much a laboratory as India for British policies with regard to land settlement, taxation, famine relief, the suppression of dissent, and much else. It is equally a highly disconcerting fact that the story of the Irish in India suggests that those who have been brutalized will in turn brutalize others. The precise role of the Irish in the colonization of India requires much further study. On the other hand, the legend of Terence MacSwiney points to the exhilarating if complicated history, which in recent years has begun to be explored by some scholars, of the solidarity of the Irish and the Indians. Indians have long been familiar, for instance, with the figure of the Irishwoman Annie Beasant, but transnational expressions of such solidarity took many forms. At a time when the world seems convulsed by insularity and xenophobic nationalism, the story of MacSwiney points to the critical importance of sympathy across borders.

Georgian translation by Ana Mirilashvili available here.