A number of my friends, acquaintances, and students have emailed me an article that appeared in the New York Times business pages on November 28, entitled ‘Some Indians Find It Tough to Go Home Again’. The article, which chronicles the difficulties that some well-intentioned Indians have encountered in their efforts to relocate to India, has evidently created something of a buzz. No one even a decade ago would have expected that Indian Americans, in significant numbers, would choose to return to India. The call of the ‘motherland’ may have always been there in the abstract, but even among those who thought of their stay in the US as a brief sojourn in their lives, and who seemed determined to render service to the motherland, the return to India was always deferred. Inertia and laziness have a way of taking over one’s life; but, for many others, the moment when the gains of a professional career, built painstakingly through dint of hard work and a relentless commitment to ‘achievement’, could be abandoned seemed not yet to have arrived.

There was a time when ‘brain drain’ could mean only one thing. Indians educated at the expense of the Indian state flocked to the US, and by the late 1980s there were enough graduates of the Indian Institutes of Technology settled in the US that one could speak of the American IIT fraternity. Ten years after ‘the economic reforms’, the benign phrase used to characterize the jettisoning of the planned economy and all pretensions to some measure of social equality, first commenced in the early 1990s, there was some mention of the trickle of Indians who had finally elected to test the waters of the ‘new India’. No one is characterizing that trickle as a stream, much less a raging river, but increasingly in India one hears these days not only of those who left for the US but of those who have abandoned the predictable comforts of American life for the uncertainties of life in India. And, now, to come to the subject of the New York Times’ article, some of the returnees to India are making their way back to the US. The motherland, apparently, has not done enough to woo the discerning or ethical-minded Non-Resident Indian.

Shiva Ayyadurai, the New York Times tells us, left India when he was but “seven years” old, and he then took a vow that he would return home to “help his country”. Why is it that, upon reading this, I am curiously reminded of contestants in Miss World or Miss Universal pageants, who have all been dying to save the world, whose every waking moment has been filled with the thought of helping the poor beautiful children of this world? My eight-year old has certainly never taken a vow that even remotely seems so noble-minded, but then who am I to judge the ethical precociousness of a seven-year old who, perhaps putting aside his toys, had resolved to “help his country”. The young Bhagat Singh, let us recall, was no less a patriot. Almost forty years later, Mr Ayyadurai, now an “entrepreneur and lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology”, returned to India, in fulfillment of his vow, at the behest of the Government of India which had devised a program “to lure talented scientists of the so-called desi diaspora back to their homeland”. Mr Ayyadurai left with great expectations; he seemed to have lasted in India only a few months. “As Mr Ayyadurai sees it now,” writes our correspondent, “his Western business education met India’s notoriously inefficient, opaque government, and things went downhill from there.” Within months, Mr Ayyadurai and his Indian boss were practically at each other’s throats: the job offer was withdrawn, and Mr Ayyadurai once again found himself returning ‘home’ – this time to the US.

One cannot doubt that the culture of work in the US and India is strikingly different, even if the cult of ‘management’ has introduced a cult of homogeneity that would have been all but unthinkable a decade ago. The account of the difficulties that Indian Americans encounter upon their attempt to relocate to India sometimes reads like the nineteenth-century British colonial’s narrative about the heat and dust of the tropics, the intractability of the ‘native’, and the grinding poverty – to which today one might add the traffic jams, pollution, electricity breakdowns, water shortages, and a heartless bureaucracy. The “feudal culture” of India, Mr Ayyadurai is quoted as saying, will hold India back. How effortlessly Mr Ayyadurai falls into those oppositions that for two centuries or more have characterized European (and now American) representations of India: feudal vs. modern, habitual vs. innovative, chaotic vs. organized, inefficient vs. efficient, and so on. Nearly every aspect of this narrative has been touted endlessly. The only difficulty is that by the time India catches up with the United States, with the West more broadly, the US will have moved on to a different plane.

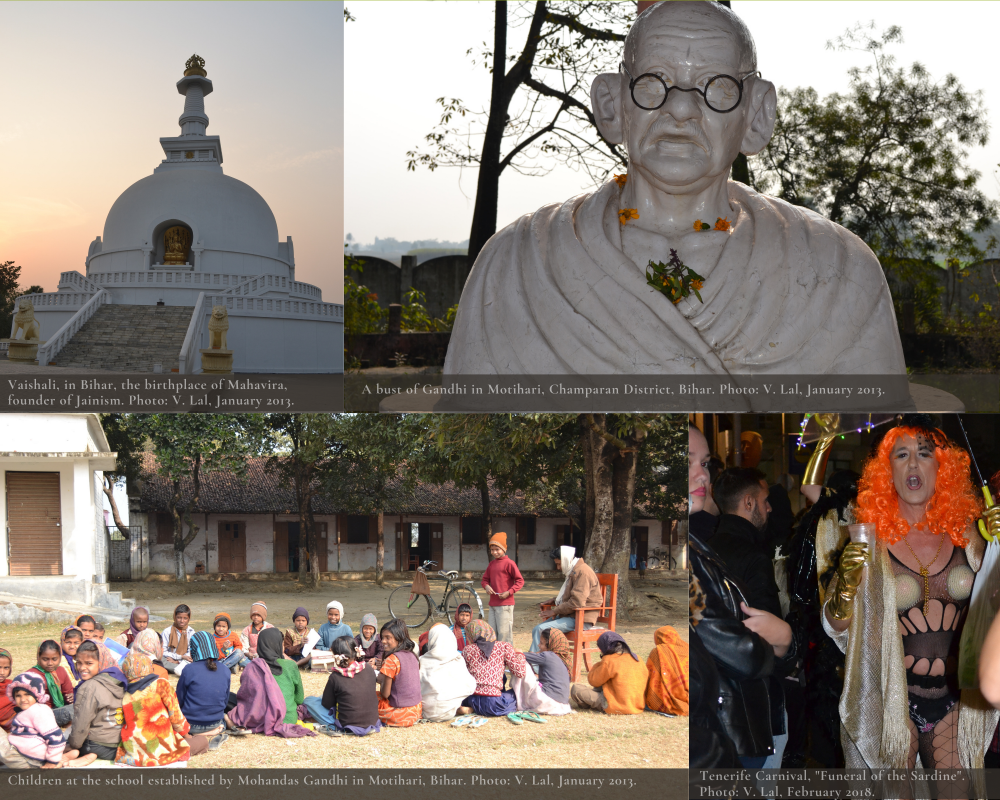

In all this discussion about home, the mother country, and the diaspora, almost nothing is allowed to disturb the received understanding of what, for example, constitutes corruption, pollution, or inefficiency. There is no dispute in these circles of enlightened beings that Laloo Yadav is corrupt, but the scandalous conduct of most of the millionaires who inhabit the corridors of power in Washington passes, if at all it is noticed, for ‘indiscretions’ committed by a few ‘misguided’ politicians. I wonder, moreover, if Laloo’s corrupt politics kept the state of Bihar free of communal killings – a huge contrast from the ‘clean’ and ‘developed’ state of Gujarat, where a state-sponsored pogrom in 2002 left over 2,000 Muslims dead. Gujarat is the favorite state of the NRIs and foreign investors, though the sheer dubiousness of that distinction has done nothing to humble either party. Or take this example: the US has done much (if not enough) to tackle pollution at home, but its shipment of hazardous wastes to developing countries is evidently a minor detail. And one could go in this vein, ad infinitum, but to little effect. The more substantive consideration, perhaps, is that there is little recognition on the part of many NRIs that there is a sensibility which still resists the idea that the conception of a home is merely synonymous with material gains, bodily comforts, or a notion of well being that is defined as an algorithm of numbers. William Blake, when asked where he lived, answered with a simple phrase: ‘in the imagination’.

On the subject of home, let me allow the 12th century monk of Saxony, Hugo of St. Victor, the final words: “It is, therefore, a source of great virtue for the practiced mind to learn, bit by bit, first to change about invisible and transitory things, so that afterwards it may be able to leave them behind altogether. The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land. The tender soul has fixed his love on one spot in the world; the strong man has extended his love to all places; the perfect man has extinguished his.”