(Seventh in a series of articles on the implications of the coronavirus for our times, for human history, and for the fate of the earth.)

Part II of “A Global Pandemic, Political Epidemiology, and National Histories”

“The Tavern Scene”, also known as “The Orgy”, third in a series called “The Rake’s Progress”, painting by William Hogarth, 1735, from the collection of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

The diary of Samuel Pepys, which gives us unusual insights into everyday life in London among the upper crust during the Great Plague, raises some fundamentally interesting questions about what one might describe as national histories and the logic of social response in each country to what is now the global pandemic known as COVID-19. The diary is taken by social historians to be the supreme example of the English sensibility at work, a claim that may appear to be controverted in my suggestion that much in Pepys’ representation of what the plague wrought appears to anticipate the questions that are being asked the world over in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. It may appear to be the case that I am advocating for the view that if one has seen one plague, one has seen all; quite to the contrary, we ought to take seriously the view commonly encountered among epidemiologists, “If you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic.” The so-called Spanish influenza of 1918-19 was, for reasons that have not been entirely understood to the present day, especially fatal to young men in their 20s and 30s, and even infants; on the other hand, COVID-19, though now known to strike people of all ages, has been the death knell more particularly for the very elderly. If, thus far, the advanced industrialized countries of the West appear to have borne the brunt of COVID-19, in the influenza that accompanied the “Great War” countries such as India and Indonesia, both of which were under colonial rule, and China, which was mired in poverty and deeply fractured by internal strife, suffered the most. But, these differences apart, to what extent is it possible to say that the Englishness of the English informed Pepys’ thinking as it does of the English at present, and that the American, French, Chinese, Indian, or other responses to the coronavirus pandemic have, in turn, been shaped both by the contours of national histories and the sensibilities born of sharply varying conceptions of ‘culture’ and ways of experiencing notions of self, identity, and community.

The World Health Organization has from the outset of the pandemic pushed for “social distancing” as a universal protocol and national governments have generally followed suit, prescribing it to different degrees and designating the measures that have restricted the movements of people, confined them largely to their homes, and strangulated the public sphere under various names such as “lockdown”, “shelter-in-place”, “stay-at-home”, and “Movement Control”. Yet, days before Britain on March 20th fell in with the rest of the world and Boris Johnson called for the closure of all non-essential businesses and a ban on public meetings, the British government had signaled its intention to defy the widely accepted international protocol on social distancing and continue to permit limited social gatherings and keep Britain, to use the clichéd expression, open for business. As Sir Patrick Vallance, the chief scientific adviser to the British government, explained on Sky News, draconian measures designed to keep people entirely confined to their homes might work for a period of time, but the virus was bound to return once those restrictions were lifted. Besides, as the Prime Minister had said, the British public would experience “behavioral fatigue” if they could not exercise their freedoms. If, on the other hand, the onset of infections could be staggered by not shuttering the economy, thereby also relieving health systems of a crushing load of cases, “herd immunity” might develop among the people.

The public commentary on Great Britain’s “herd immunity” debacle has been profuse, but nearly without exception it has focused both on the quite possibly flawed epidemiological understanding of COVID-19 and the poor messaging of the government. It is vaccination that typically generates herd immunity, and the notion that an immune population might be created by a lethal infectious agent opens up the possibility that some lives, perhaps a great many lives, are viewed as expendable. On March 12th, while warning the British public that the country faced “the worst public health crisis for a generation” and that “many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time”, Prime Minister Johnson nevertheless said that he was neither prepared to close schools nor join Scotland in banning gatherings of more than 500 people. Johnson was prepared only to advise those over 70 that they should desist from taking cruises just as schools were to refrain from taking pupils on trips abroad. It is not in Britain alone that people were aghast at such pronouncements emanating from the highest offices of the land that seemed to suggest that the British government was aiming at creating an epidemic by having a significant portion, perhaps as much as 60 percent, of the populace get infected in the expectation that the “herd immunity” thus developed would eventually render the virus impotent.

The death toll in Britain from the coronavirus stood at 12 on March 12th; eight days later, when Johnson in a televised address to the nation declared the decision of the British government to reverse course and join the world in advocating for a total ban on public gatherings and the virtual shuttering of the economy, the number had risen to nearly 150. “We are collectively telling cafes, pubs, bars, restaurants”, Johnson said as indicated in the transcript of his remarks released by the Prime Minister’s Office, “to close tonight as soon as they reasonably can, and not to open tomorrow. . . . And listening to what I have just said, some people may of course be tempted to go out tonight. But please don’t. You may think you are invincible, but there is no guarantee you will get mild symptoms, and you can still be a carrier of the disease and pass it on to others.” Counseling, as he had done earlier in the address, the public to stay at home, Johnson had this to add: “I know how difficult this is, how it seems to go against the freedom-loving instincts of the British people.” He appears also to have said, as reported in the liberal Guardian, “We’re taking away the ancient, inalienable right of free-born people of the United Kingdom to go to the pub”, though the more conservative Sun rendered it quite differently: “Mr Johnson said he realized it [the government order] went against what he called “‘the inalienable free-born right of people born in England to go to the pub.’”

English Pubs and London’s Night Scene, before the Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020.

Let us not quibble at the moment over the differences, significant as they are, in the accounts of Johnson’s remarks as found in the Guardian and the Sun: if it is only people “born in England” who have the inalienable right to go to the pub, that would seem to exclude the millions of immigrants who have put down roots in Britain and taken citizenship, not to mention the Irish, the Scots, and the Welsh. One can scarcely imagine a more offensive remark at a time when immigrant doctors and health workers who staff Britain’s National Health Service, which Johnson has more recently thanked profusely for restoring him to health after his dangerous flirtation with coronavirus-induced death, have clearly gone out of the way to render service to a nation that has often been inclined to treat them as something little better than second-class citizens. There is yet a more grave consideration here: In Johnson’s extraordinary invocation of the restrictions demanded by the pandemic as an affront to the freedom-loving instincts of the British and most certainly English people, and as a violation of their inalienable right to the pub, we are face-to-face with the political epidemiology of COVID-19. Enough has been said by virologists, medical practitioners, and scientists about the epidemiology of the coronavirus; and increasingly, though this language is opaque to most journalists, we are also hearing a good deal about its social epidemiology and the visibly greater vulnerability of the poor, the working-class, and the socially and politically disadvantaged to COVID-19. It is Friedrich Engels who, in his majestic The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844), furnished the grounds of an incipient social epidemiology in his penetrating analysis of the greater susceptibility of the working class to deprivation, desolation, and disease. The “usual consequences of inhaling factory dust”, he wrote in a characteristically blunt passage on the workers of Manchester amongst whom he lived and worked for two years, “are the spitting of blood, heavy, noisy breathing, pains in the chest, coughing and sleeplessness.” It is in fact social epidemiology that is now helping us to chart the disproportionately detrimental effects of COVID-19 as it makes its way across prison populations, slums, chawls, ghettos, favelas, banlieues, shantytowns, immigrant neighborhoods, and working-class enclaves. [For an excellent discussion of what Engels saw in Manchester, the reader is referred to Howard Waitzkin, “The Social Origins of Illness: A Neglected History”, in Embodying Inequality: Epidemiologic Perspectives, ed. Nancy Krieger (Routledge, 2016.]

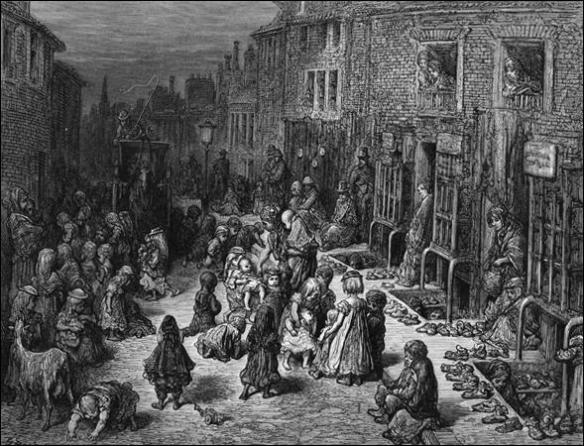

London, by Gustave Dore (1872).

Political epidemiology, however, takes us still further afield to a larger set of questions on how national histories and conceptions of national character have shaped the response of politicians and the populace alike to the coronavirus across countries and political systems. England has long prided itself on its essential distinction from everyone else, but nothing is more critical to English political life and self-awareness than the idea that it is apart from continental Europe even as it partakes fully of the legacies of Western civilization. The idea—the Englishness of the English—is present in Shakespeare; it is there in the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens; and it was cemented by what is commonly thought to be, and has in England itself been represented as, the crowning moment of glory in Britain’s modern history as it became the vanquisher of a militant Germany in World War II. The Nazis took Paris almost effortlessly, a palpable demonstration (though this was not always loudly proclaimed) of Gallic effeminacy and cowardice: all that stood between civilization and barbarism, as the English would come to believe, was their own indomitable will to resist naked militarism and keep out the barbaric German invader. Some have characterized the English demeanor through the expression, “the stiff upper lip”, but it is perhaps better captured in the storied history of the Londoner’s stoic and yet nonchalant resistance to the carpet bombing of their city. People went into the Underground as the bombs incessantly rained down on their beloved city; once the air raid siren sounded the “all clear”, they emerged into the streets—and headed for the ale-house, Boris Johnson’s much vaunted “pub”.

“Behind the Bar”, a painting by John Henry Henshall, 1883.

“No man is an island entire of itself”, John Donne famously wrote, but the notion of Great Britain as an island complete unto itself, standing forth as something like the Rock of Gibraltar, never more so than in the face of adversity, has been pervasive in the history of English self-representation. It has played a significant part in fueling Britain’s exit from the European Union, just as it informs both Boris Johnson’s initial decision to separate Britain from the herd, ironically in the name of attempting to have the British acquire “herd immunity”, and later his seemingly quaint invocation of the “inalienable right” of the English—or did he say British, which is quite a different thing, when one considers the history of England’s suppression of Scotland, or the virulent English hatred until comparatively recent times of the Irish as infernal Papists—to “go to the pub”. George Orwell was mindful of “the insularity of the English, their refusal to take foreigners seriously”, but if this has been “a folly that has to be paid for heavily from time to time” he also thought that the same characteristic had helped to “keep out the invader.” Orwell’s war-time essay, “England Your England”, is a paean to this very Englishness: “When you come back to England from any foreign country, you have immediately the sensation of breathing a different air.” The feeling one has in England is bound up “with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes”—and, above all, with the awareness that this is one country where “the liberty of the individual is still believed in”, a liberty which has “nothing to do with economic liberty, the right to exploit others for profit”, but rather the liberty “to have a home of our own . . . to choose your own amusements instead of having them chosen for you from above”. The freedom-loving instincts of the English people send them, Boris Johnson has told us, to the pub and the coronavirus pandemic must not be permitted to strip them of this ancient right: as Orwell put it, the culture of England has hovered around the “pub, the football match, the back garden, the fireside and the ‘nice cup of tea.’”

(to be continued)

See also Part I, “Life in the Time of Plague: Samuel Pepys in London, 1663-66”, here.

Pingback: The National Imaginary: Patriots and the Virus in the West | Lal Salaam: A Blog by Vinay Lal

This is an interesting take on the role of culture in epidemiology. I feel like the phrase “nothing occurs in a vacuum” applies to this, and is similar to what you mentioned in the beginning of the post, that “if you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic”. The culture of both the time, and the individual country will have a vast impact on the trajectory of the pandemic. One thing that shocked me about the pandemic in America was people’s refusal to wear a mask. When I lived in Japan, it was standard that you wore a mask if you had even the common cold, and I was taken aback by the general courtesy people had for others. Because of this, it was completely astonishing the me watching my fellow Americans refuse to take the simple action of mask wearing to protect others. It made me realize what an impact different cultures and community has on different events.

LikeLike

Having lived in England when the pandemic began, I find your analysis of the cultural response to it very accurate. I remember the emphasis on herd immunity as well as when the country shifted to stringent measures. Interestingly, you mention the connection between English nationalism and their response to the pandemic. I believe that the herd immunity response comes from the sentiment that the UK is distinctly its own and able to forge its path regardless of what is happening in other countries. This is evidenced by Brexit, as the UK has decided they no longer need to be part of the European Union and consequently doesn’t need to be considered part of Europe. The UK has a strong emphasis on independence in crisis. I think this would make people in the UK believe in herd immunity because they have great pride in being English and the English ability to overcome that which other countries cannot. I find your analysis of pub culture very compelling as well: the sentiment that pubs are distinctly English, and a symbol of national pride, explains why people were so resistant to social distancing measures. They felt as if their cultural identity was being taken away. I think that not wanting to comply with social distancing measures added to people’s belief in the herd immunity theory because it was a strategy that allowed them to keep their cultural identity intact.

LikeLike